Accessibility

Introduction

The web is changing fast. In 2025, web accessibility matters more than ever as mainstream technologies increasingly rely on inclusive features. For example, voice-activated assistants use screen reader technologies. Features originally designed for accessibility, such as video captions and haptic feedback, are now common.

Universal Design principles are fundamentally important for our work in modern web development. We’re increasingly creating solutions that address diverse needs and improve experiences for all users. As Sir Tim Berners-Lee famously said, “The power of the Web is in its universality. Access by everyone regardless of disability is an essential aspect.”

Recent global events and shifting legal requirements have pushed digital inclusion into focus. Microsoft’s Inclusive Design Guidelines show that accessibility helps more than just people with permanent disabilities. The guidelines specifically mention temporary and situational limitations. For example, the ability to use a device with one hand can help individuals with injuries, parents with young children, as well as people carrying items.

In 2025, web accessibility laws have real teeth. The European Union’s (EU) European Accessibility Act (EAA) is a major step forward. It set a deadline of June 2025 for numerous websites and apps to conform to the EN 301 549 standard, which references the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG).

The United States updated its regulations as well. State and local government sites must now meet WCAG 2.1, as required by Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act. The 2024 data gives us a critical baseline to measure the tangible impact of these deadlines on the accessibility of websites globally.

Google Lighthouse powers our analysis using Deque’s axe-core engine. We benchmark 2025 findings against 2024 data and identify key trends. With broader adoption of WCAG 2.2, we examine the uptake of new Success Criteria and continued changes from deprecated rules such as duplicate-id.

Our approach is similar to that of the WebAim Million but with differences in sites crawled and analysis tools used. The HTTP Archive crawls 17 million sites each month across home and secondary pages using Lighthouse and other tools. WebAim surveys the top million home pages with WAVE.

Automated tests, including axe-core which is used by Lighthouse, can only partially check a subset of WCAG Success Criteria. Alphagov from GOV.UK offers a comparison of popular automated audit tools and they all detect less than 50% of accessibility errors. Many criteria lack automated tests altogether, and not all accessibility issues have matching criteria in WCAG.

But remember Goodhart’s Law. When a metric becomes a target, it stops being a reliable metric. A perfect score doesn’t guarantee full accessibility. You should treat Lighthouse accessibility scores as a starting point for evaluation rather than a final goal. Still, tracking these scores offers a valuable snapshot of the web’s overall progress.

Our report focuses exclusively on HTML and doesn’t include PDF or other office documents.

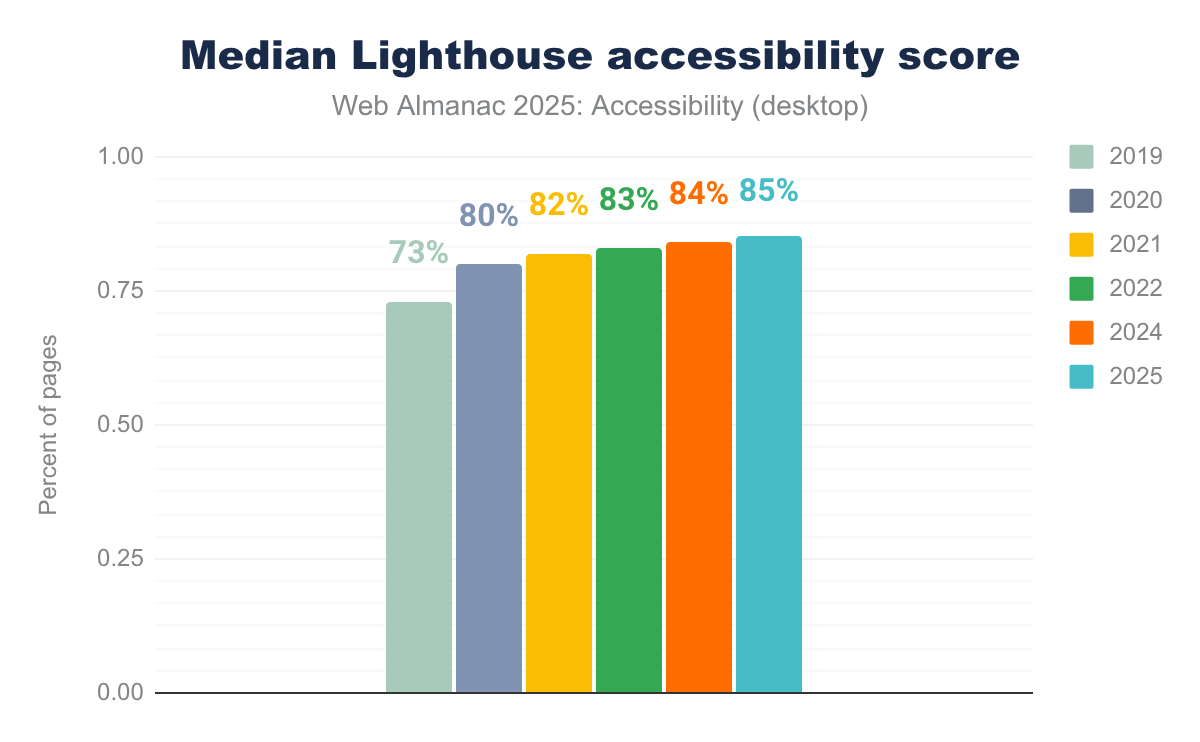

Compared to 2024, the median Lighthouse Accessibility score improved by 1%, reaching over 85% in 2025. Since the first Web Almanac in 2019, we’ve seen steady and incremental progress. Google Lighthouse assigns different weights to axe-core issues, so organizations may prioritize fixes differently.

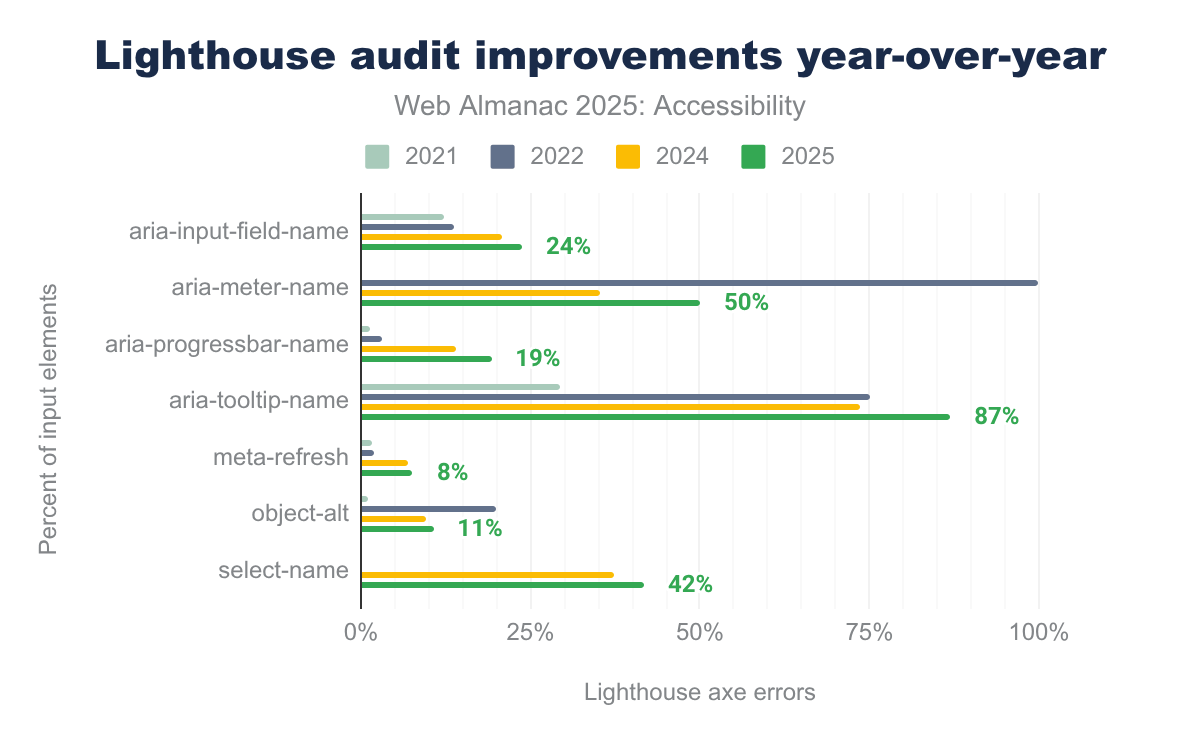

This year, we’ve seen the biggest advances in the following axe-core tests:

- ARIA input fields must have an accessible name: +3% over 2024

-

ARIA

meternodes must have an accessible name: +15% over 2024 -

ARIA

progressbarnodes must have an accessible name: +5% over 2024 -

ARIA

tooltipnodes must have an accessible name: +13% over 2024 - Avoid delayed refresh under 20 hours: +1% over 2024

-

<object>elements must have alternate text: +1% over 2024 -

<select>element must have an accessible name: +5% over 2024

aria-input-field-name, in 2021 12%, in 2022 14%, in 2024 21%, and in 2025 24%. For aria-meter-name, in 2021 0%, in 2022 100%, in 2024 35%, and in 2025 50%. For aria-progressbar-name, in 2021 1%, in 2022 3%, in 2024 14%, and in 2025 19%. For aria-tooltip-name, in 2021 29%, in 2022 75%, in 2024 74%, and in 2025 87%. For meta-refresh, in 2021 and 2022 2%, in 2024 7%, and in 2025 8%. For object-alt, in 2021 1%, in 2022 20%, in 2024 10%, and in 2025 11%. For select-name, in 2024 37%, and in 2025 42%.This year, we’re adding a new chapter on Artificial Intelligence (AI) to the Web Almanac. AI is changing how we build websites, write code, generate content, optimize performance, and interact with interfaces. It already plays a growing role in accessibility work, from generating image descriptions and captions to assistants that help teams find and fix issues.

At the same time, AI introduces risks and unanswered questions. There’s no reliable way yet to see when AI has created or assisted in creating a website. Language models are trained on code and content that often contain accessibility problems. Automated descriptions or patterns can easily miss context, user intent, or nuance. Broader concerns about data use, environmental impact, and encoded bias directly affect who benefits from AI on the web and who is harmed or excluded.

The new AI chapter explores these tensions: how AI is already helping teams, where it falls short, and what standards, safeguards, and practices are needed. One principle runs through the analysis: AI should support human expertise and inclusive design, not replace them.

Throughout this chapter, you will find actionable links and practical solutions to help you improve accessibility on your own sites.

Ease of reading

Users need to easily read and understand web content. This goes beyond picking legible fonts. It also covers using clear language, organizing pages logically, and following predictable design patterns.

While this report focuses on measurable technical metrics, qualitative factors, such as writing in plain language, matter just as much. WCAG 3.0 is exploring how to incorporate requirements for clear language, but it’s still in the development phase.

Similar to plain language, numbers pose their own accessibility challenges. Some users struggle to interpret them, and automated tests can’t reliably catch this as a barrier. To address this, review resources like Accessible Numbers for practical advice on presenting numeric information clearly on the web.

Readability metrics exist for English content. The Flesch-Kincaid readability score is one example. But the web is global. It spans many languages and diverse audiences. No standardized automated test covers all cases or languages.

Color contrast

The difference between foreground and background colors determines whether people can perceive web content. Insufficient color contrast remains a common barrier, especially for users with low vision or color vision deficiencies.

Color contrast is especially important for older users, people with temporary disabilities, like missing reading glasses, and anyone reading under bright sunlight or in challenging environments.

WCAG requires contrast ratios of at least 4.5:1 for standard text and 3:1 for large text to achieve AA conformance. AAA conformance demands 7:1 for normal text. WCAG contrast ratios are an important baseline, but these guidelines don’t address every form of color blindness or individual variation in perception.

Other documents, including the Accessible Perceptual Contrast Algorithm (APCA), aim to offer a more perceptually accurate measurement of contrast.

Open source tools, like the newly released Contrast Report, make it easier than ever to find and fix color contrast issues. They even suggest modifications when colors fail to meet required ratios. For additional guidance, you can consult expert resources, such as Dennis Deacon’s article on color contrast testing.

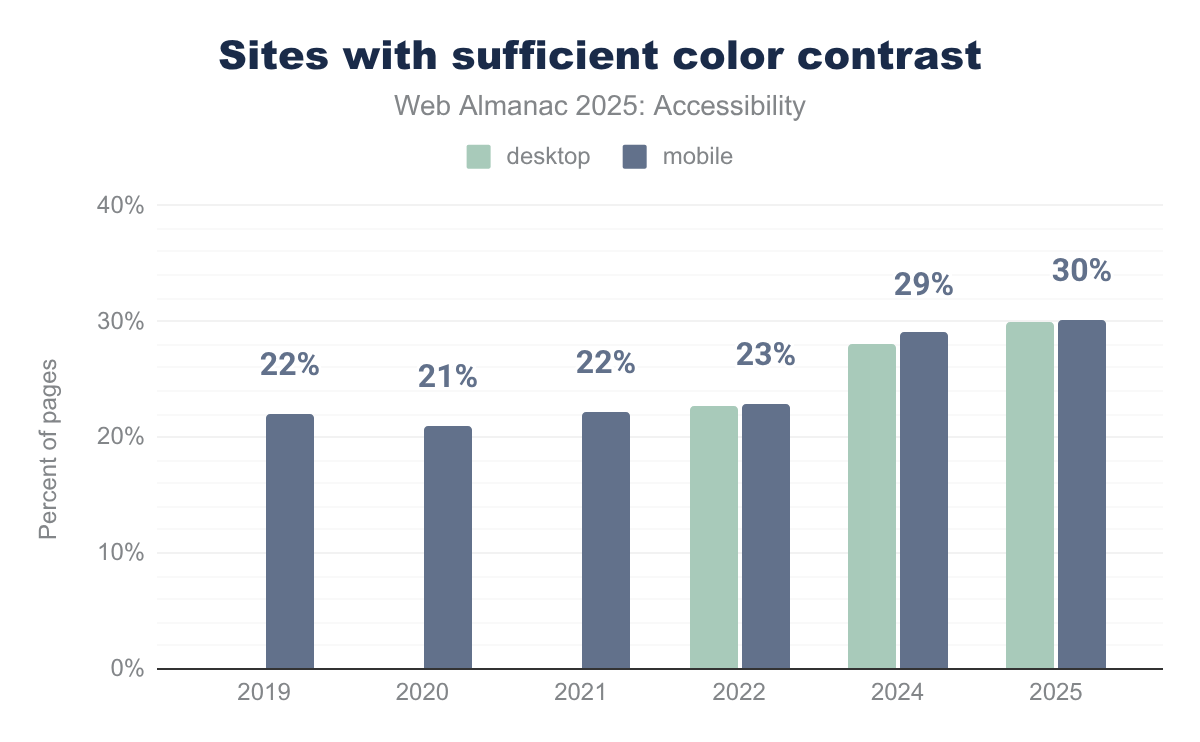

This year, text contrast pass rate improved by roughly 1% compared to 2024. But only 31% of mobile sites currently meet minimum color contrast requirements. Since mobile experiences depend heavily on clear visibility, this gap is a real problem for users accessing the web on their phones.

Browsers and operating systems increasingly support light, dark, and high-contrast modes. Users have more control now. Most sites still don’t respond to these preferences though.

Zooming and scaling

Users must be able to resize content to suit their needs. Disabling zoom removes user control and is a direct violation of WCAG resizing requirements. This is more than a minor inconvenience. It may make a site completely unusable for people with low vision or those who rely on screen magnification for reading.

In 2025, this restrictive pattern still appears, often because developers want pixel-perfect layouts on mobile devices. Unfortunately, that comes at the cost of usability and accessibility.

The number of sites that disable zooming or scaling continues to drop. In 2025, only 19% of mobile sites and 21% of desktop sites restrict scaling, either by using user-scalable=no or setting a restrictive maximum scale. That’s a 1–2% improvement over 2024, showing slow but steady progress.

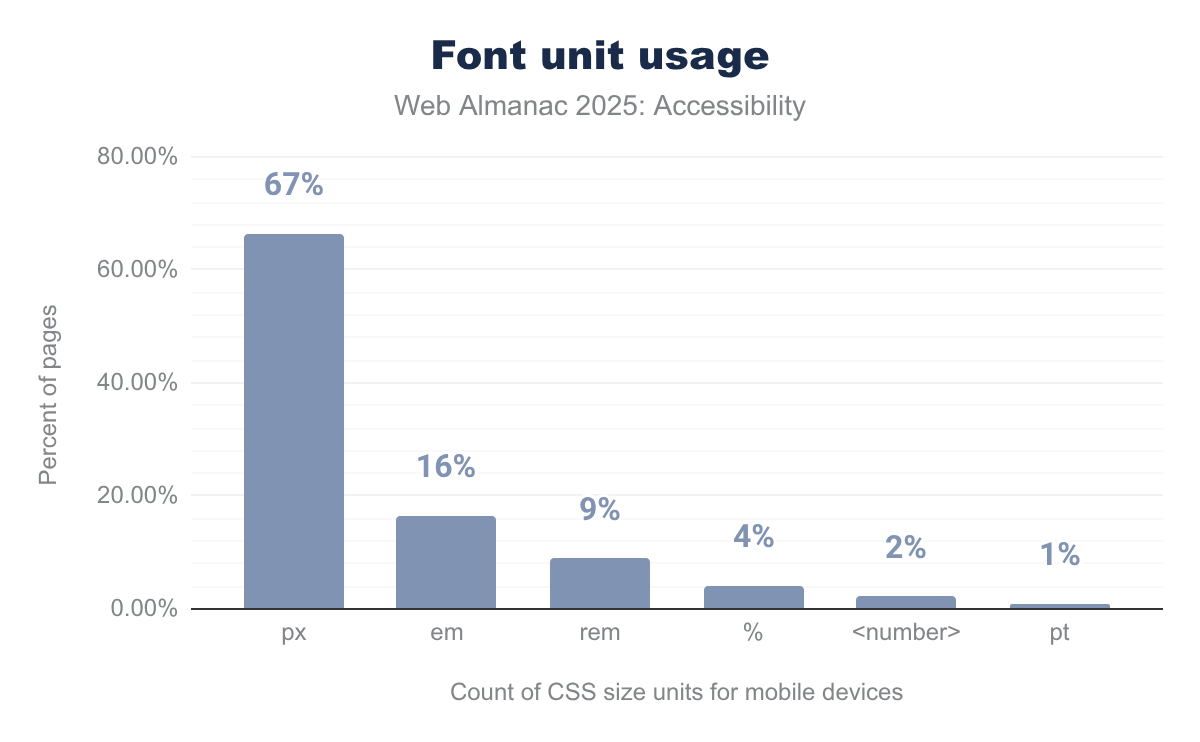

px is used for font sizes on 67% of desktop, em on 16%, rem on 9%, percentages on 4%, <number> on 2%, and finally pt on 1% of websites tested.Font size units directly affect how text can respond to user preferences. Relative units, such as em and rem, let text to scale predictably with browser settings. In 2025, the use of em on mobile sites increased by 2%, improving user experiences for those who adjust font sizes to increase readability. Otherwise, font size unit usage stays largely the same as last year.

If you want to check whether your site is restricting zoom, examine its source code for the <meta name="viewport"> tag. Avoid using values like maximum-scale, minimum-scale, user-scalable=no, or user-scalable=0, as these limit resizing. Instead, let users freely adjust content size. WCAG requires that text can resize up to 200% without loss of content or functionality.

Language identification

Declaring a page’s primary language with the lang attribute is essential. It lets screen readers select the correct pronunciation rules and enables browsers to provide more accurate automatic translations. Beyond the primary language, it’s equally important to specify the language of sections that differ from the main language. This ensures that screen readers properly switch pronunciation for foreign words or phrases.

Despite being a straightforward Level A WCAG requirement, language declaration remains an area where many sites fall short. In 2025, roughly 86% of sites include a valid lang attribute, largely unchanged from 2024. This suggests steady adoption but also highlights room for improvement.

Correctly applying the lang attribute begins with including it on the <html> tag to specify the page’s primary language. Pages often contain multiple languages. Use the lang attribute on individual elements or sections as needed. The W3C’s documentation on specifying the language of parts provides detailed guidance on this topic.

Missing or incorrect language declarations can cause translation errors.

For example, Chrome’s automatic translation might misinterpret page content without a declared language, leading to confusing or inaccurate translations. Proper language tagging also supports styling for right-to-left languages and other language-specific behaviors.

User preference

Modern CSS includes User Preference Media Queries that let websites adapt to a user’s operating system or browser settings. Users get a more comfortable, personalized experience. Websites can respond to preferences for motion, contrast, and color schemes.

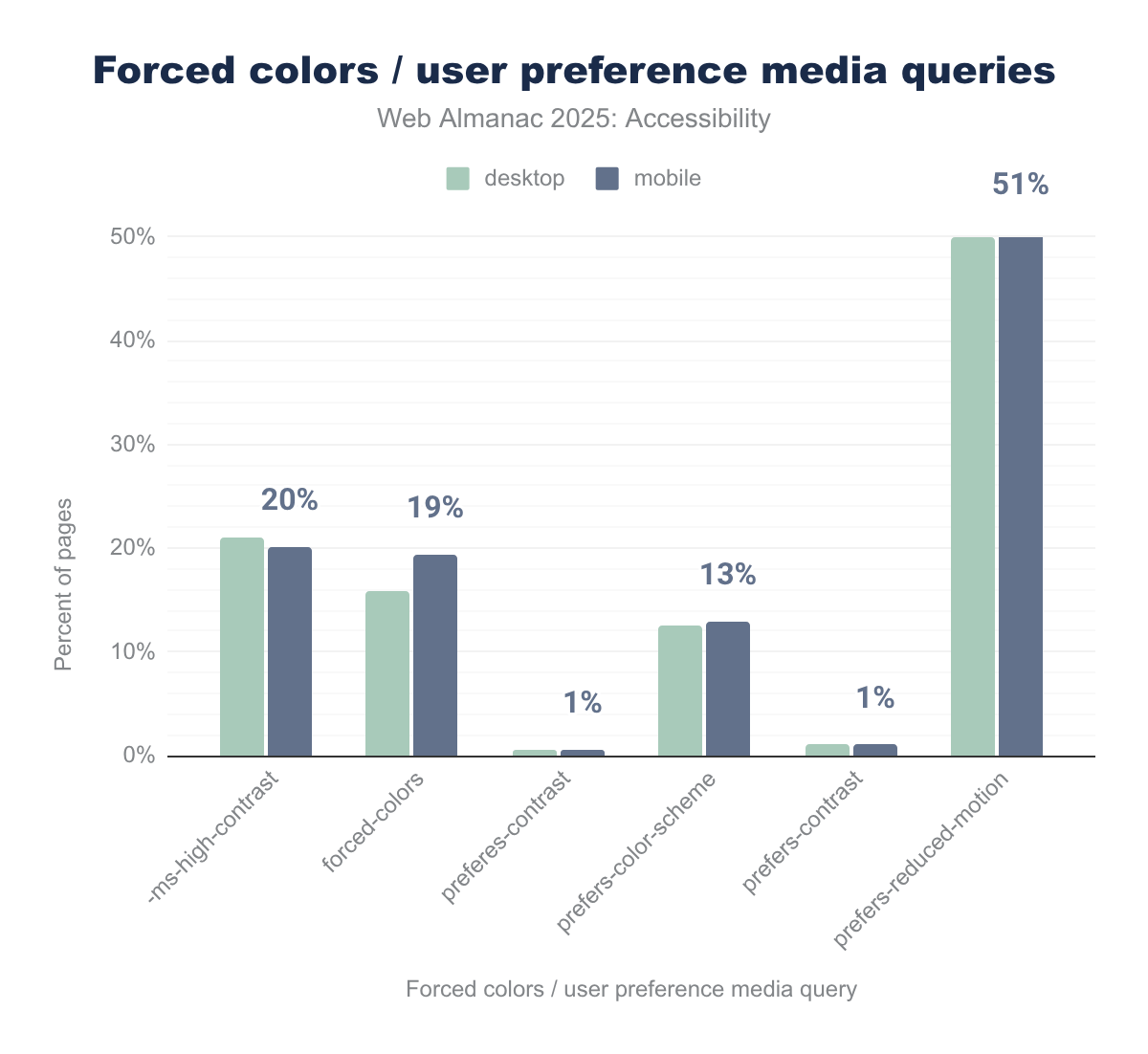

prefers-reduced-motion, appearing on about half of both desktop (49.99%) and mobile (50.55%) pages. -ms-high-contrast and forced-colors also show notable usage, at around 21% and 16% on desktop and 20% and 19% on mobile, respectively. Other features, such as prefers-color-scheme (about 13% on both platforms) and prefers-contrast (around 1%), are used much less, while several legacy or experimental features appear on virtually no pages.The most familiar queries, prefers-reduced-motion and prefers-color-scheme, remain widely supported by browsers. In 2025, adoption of these queries by websites shows little change. However, the use of forced-colors, which supports high-contrast modes for users with low vision, increased by 5% to 19%. Meanwhile, use of the outdated -ms-high-contrast media query has declined by 3% down to 20%. This reflects a gradual shift towards modern CSS standards.

Continuing to incorporate these preferences advances accessibility and user satisfaction by respecting individual needs and system settings.

Broader implementation of personalization through CSS media queries hasn’t seen significant growth despite these incremental gains. Encouraging further adoption helps ensure websites honor users’ preferences, including reducing motion for vestibular disorder sensitivities and adapting display colors or contrast for visual comfort.

Navigation

Users navigate websites in different ways. Some use a mouse to scroll. Others use a keyboard, switch control device, or screen reader to navigate through headings. An effective navigation system must work for every user, regardless of their input device.

Wide-screen TVs and voice interfaces like Siri and Amazon Alexa create unique navigation challenges. Building good semantic structure into a site helps screen reader users navigate. It also helps users of many other types of technology.

Focus indication

Focus indication is essential for users who rely primarily on keyboard navigation and assistive devices to move through web content. It provides a visible cue that highlights which element is currently focused, so users understand where they are on the page.

Automated testing tools like Google Lighthouse can identify many basic requirements and flag obvious failures around focus indicators. But they’re limited when it comes to complex interactions like keyboard traps, focus order, and whether focus moves logically to new content. Passing automated audits doesn’t guarantee a site’s keyboard accessibility or a good user experience for keyboard users.

Comprehensive manual testing is irreplaceable.

Tools like the open source Accessibility Insights for the Web extension leverage Deque’s axe-core and offer guided manual tests. The “Tab Stops” visualization feature helps testers see the path keyboard users take and identify potential issues effectively, like missing focus styles or unexpected focus traps.

Users of alternative navigation devices with limited motor abilities have unique needs related to focus visibility and sequence. Customizing assistive technology interfaces helps maximize control tailored to their abilities.

Focus testing best practices include:

- No focus traps where keyboard users get stuck

- All interactive controls are keyboard focusable

- Tab order is logical and intuitive

- Focus is appropriately directed to new or dynamically loaded content

The A11y Collective’s report on understanding focus indicators offers practical insights for implementing and testing visible focus outline styles.

Focus styles

WCAG mandates that all interactive content must have a clearly visible focus indicator. This visual cue helps keyboard users identify which element is currently focused as they move through the page.

Without a prominent focus indicator, keyboard users and those relying on assistive technologies can easily become lost. Robust focus styles, like a high-contrast outline, are fundamental to accessible design. Many institutions, like GOV.UK, have established standards for focus indicators to ensure consistency and clarity.

Design annotations need to specify keyboard interactions, as Craig Abbott clearly laid out in the TetraLogical blog. Shortly after this post, GitHub released their accessibility Annotation Toolkit, addressing the same problem.

:focus selector is present on about 90% of both desktop and mobile pages, while removing focus outlines with :focus { outline: 0; } appears on roughly two-thirds of pages (67%) for both. Usage of the more accessible :focus-visible selector is much lower, at about one-quarter of pages (25% on desktop and 24% on mobile).In 2025, 67% of sites explicitly removed default focus outlines, up 14% from 2024. This concerning trend may impair accessibility if not replaced with effective styles. On the positive side, adoption of the :focus-visible pseudo-class has grown. This means developers are starting to create context-aware focus indicators that are visible only when necessary.

tabindex

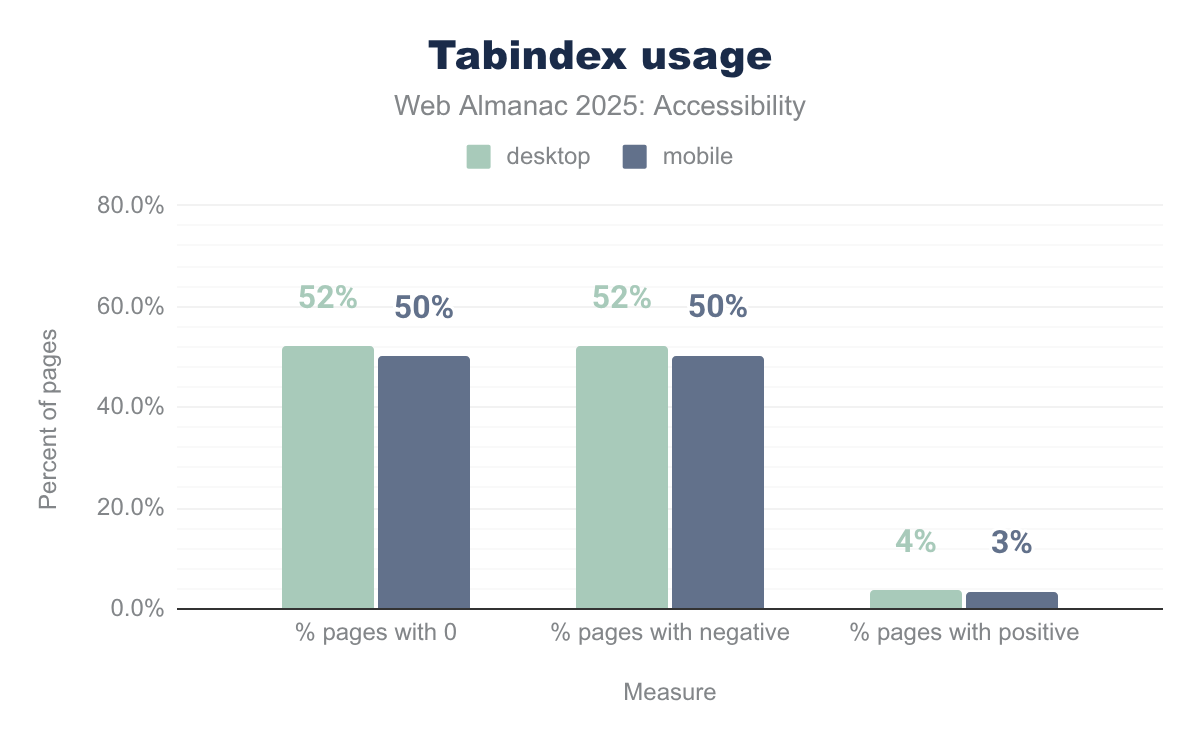

The tabindex attribute controls an element’s participation in the keyboard focus order. It lets developers include, exclude, or reorder focusable elements. Correct use supports logical navigation and accessibility, and is a WCAG requirement. Misuse, especially with positive values, can disrupt natural tab order and confuse users.

tabindex values on desktop and mobile. Just over half of pages use 0 (52.1% on desktop and 50.1% on mobile), and a similar share use negative tabindex values such as -1 (52.0% on desktop and 50.3% on mobile). In contrast, positive tabindex values appear on only a small minority of pages (3.7% on desktop and 3.4% on mobile).tabindex usage.

In 2025, tabindex usage has increased slightly. Just over 50% of sites used it, around 3-4% higher than 2024. Positive tabindex use remains stable, generally low, reflecting continued awareness that positive tabindex values should be avoided.

Landmarks

Landmarks structure a web page into distinct thematic regions, using native HTML elements such as <header>, <nav>, <main>, and <footer>. These elements create a clear, high-level page outline that help users of assistive technologies quickly understand the layout and jump directly to relevant sections.

A common accessibility anti pattern persists when developers add redundant ARIA attributes. For example, adding role="navigation" to a <nav> element. The <nav> element inherently carries the navigation role, so this duplication adds clutter to the code without benefit and may confuse assistive technology. Best practice is to favor native HTML5 elements first before adding ARIA landmark roles. That’s ARIA’s primary guideline.

Accessibility experts like Eric Bailey have highlighted the pitfalls of overusing ARIA in contexts where native semantic HTML is enough. Heydon Pickering’s twelve principles of web accessibility also emphasize the critical role semantic structure and landmarks play in accessible navigation.

| Element | Element % | Role % | Both % |

|---|---|---|---|

| main | 40.72% | 17.81% | 47.34% |

| header | 65.99% | 10.95% | 67.41% |

| nav | 67.73% | 18.02% | 70.94% |

| footer | 66.38% | 9.59% | 67.66% |

role attributes (footer, header, main, nav) across five years. Usage has grown steadily for all roles: nav leads at 66% in 2021 rising to 71% in 2025, followed by footer (65% to 68%), header (64% to 67%), and main (35% to 47%).In 2025, the adoption of ARIA landmarks has increased slightly, led by the growing use of the native <main> element, now at 47%, up 3% from 2024. This progress reflects better compliance with semantic HTML and more robust page structure for users relying on assistive tools.

Screen reader users often navigate via “rotors” or landmark menus to jump between these page regions. Skip links pointing to landmarks improve usability by allowing immediate access to core content. They circumvent repeated navigation blocks or banners. We discuss Skip links in a later section.

Continued education on leveraging native HTML5 landmarks and minimizing redundant ARIA roles will further improve keyboard and assistive technology navigation experiences. The growth in semantic structure adoption supports accessibility goals and aligns web content with modern best practices.

Heading hierarchy

A coherent heading structure acts like a table of contents for a web page. It supports accessibility, SEO, and user comprehension. For screen reader users, navigating via headings is a key way to find information quickly. Search engines also rely on heading hierarchy to understand a page’s organization and relevance.

Headings should communicate document structure, not just visual styling. Using heading tags such as <h3> or <h4> solely for their font size breaks the logical order. It makes navigation difficult for users of assistive technologies and violates the principle of separating structure from presentation. Instead, developers should style headings with CSS and use heading tags according to content hierarchy.

For a refresher on why semantics matter, review this article by Jono Alderson.

After a multi-year decline, heading hierarchy scores improved by almost 2% in 2025, indicating a renewed focus on proper heading structure.

Nevertheless, misusing headings for styling instead of structure remains common.

Skip links

Skip links are navigation aids that allow keyboard users and others using non-mouse input devices to bypass large, repetitive blocks of content, such as site navigation menus, and jump straight to the main page content. Typically, a “skip to main content” link is present as the first focusable element on the page for efficient navigation.

Bypassing blocks of content is a WCAG requirement, and basic implementations remain the norm.

Sophisticated tools, like PayPal’s open source SkipTo, exist to generate dynamic menus of all major landmarks and headings on a page. This richer interaction benefits a wider range of users, enhancing overall navigability and usability. Eleanor Hecks wrote a compelling article on the importance of keyboard accessibility, as did TetraLogical.

Adoption of skip links has remained largely static from 2024 to 2025.

Approximately 24% of desktop and mobile pages include skip links detectable by common analysis methods. This figure might under-represent actual usage, as some skip links appear deeper in the page or target landmarks beyond navigation menus.

Document titles

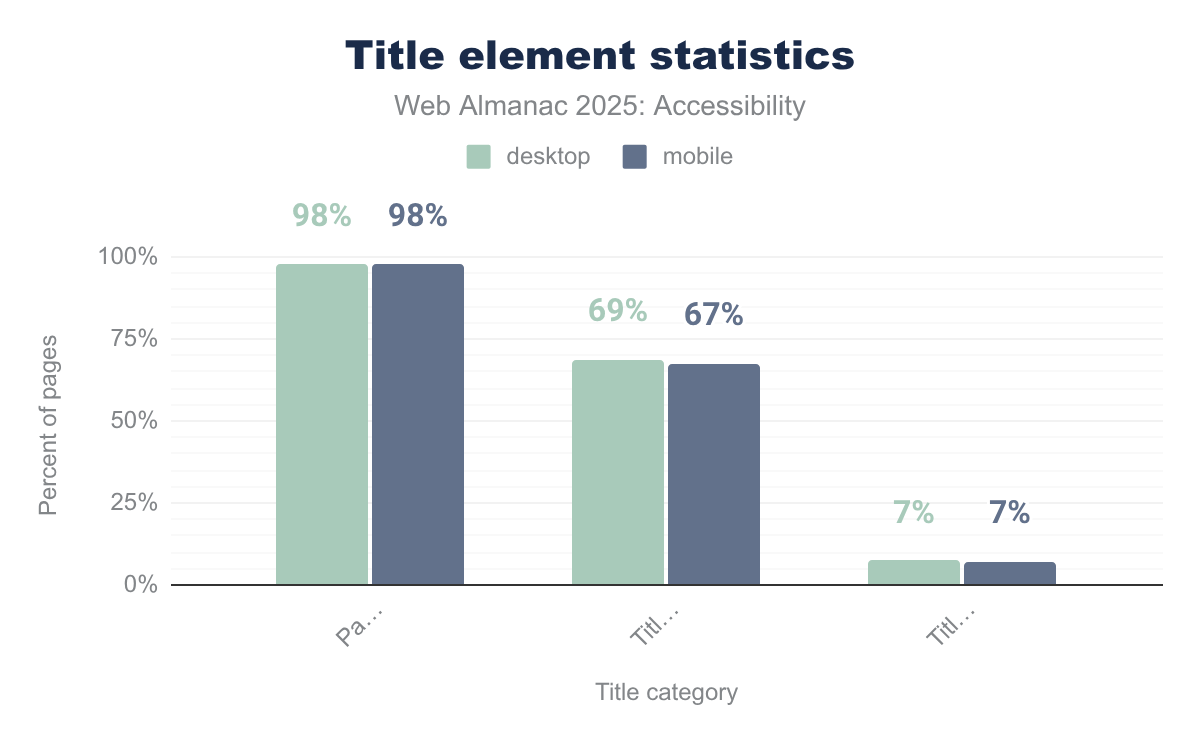

A descriptive page <title> is a basic necessity. It provides context for users navigating between browser tabs and windows and is often the first piece of information announced by a screen reader, helping users get oriented. WCAG also mandates that every page should have a meaningful title.

The 2025 data shows a slight improvement in the presence and descriptiveness of document titles compared to previous years. Approximately 98% of sites now include a <title> element, a 1% increase from 2024.

This is positive. But despite this high inclusion rate, many titles remain insufficiently descriptive. This impacts usability, especially for screen reader users who rely on clear titles for orientation.

There was a 2% decrease in mobile sites having titles with four or more words, which may indicate shorter or less specific titles on mobile pages. Including both a brief description of the page content and the website’s name remains best practice for enhancing navigation and context.

Document titles remain a fundamental accessibility feature that benefits all users. They provide context when navigating browser tabs and windows. While near-universal in presence, improving title descriptiveness and consistency continues to be an important focus in 2025 and beyond.

Tables

HTML tables present data in a two-dimensional grid. Accessibility depends on structuring them with appropriate semantic elements. Using <caption> provides crucial context for screen reader users, while <th> elements define headers for rows and columns, helping users understand relationships within the data. Steve Faulkner’s tool, released in 2025, can help developers quickly inspect the semantics of any HTML element.

The use of <caption> remained steady in 2025 compared to 2024, with only a small percentage of sites including captions. This low adoption is similar to prior years: roughly 1.6% of desktop sites include captions, which is an important, though often overlooked, accessibility feature.

Tables shouldn’t be misused for layout purposes. CSS Flexbox and Grid handle layout. When tables are used purely for layout, the role="presentation" attribute removes their semantic meaning to avoid confusion with assistive technologies.

| desktop | mobile | desktop | mobile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Captioned tables | 5.6% | 4.7% | 1.7% | 1.7% |

| Presentational table | 4.9% | 5.4% | 3.6% | 4.8% |

In 2025, 4.9% of mobile tables use this technique, up from 4% in 2024 and 1% in 2022. The emphasis remains on using semantic HTML elements correctly to make tables accessible.

Forms

Forms are how users interact with the web, from logging in to making a purchase to sharing information. Ensuring they’re accessible is critical for users to complete tasks and participate fully online.

<label> element

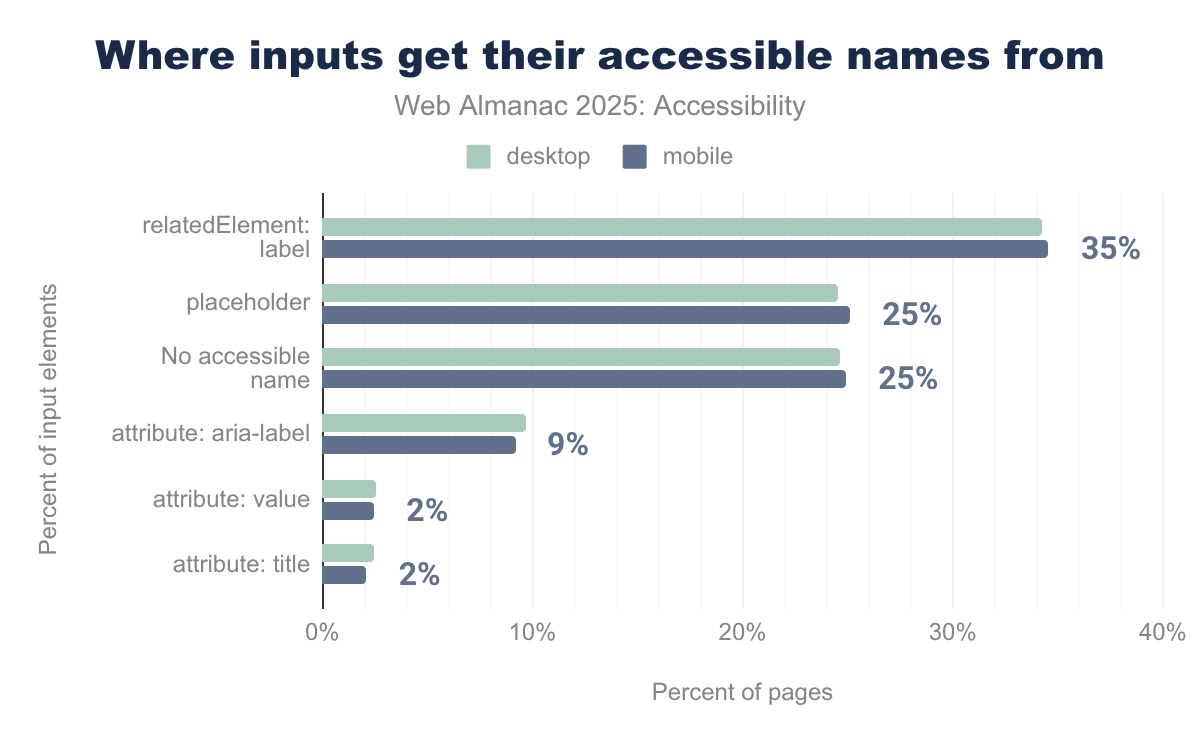

The <label> element remains the standard, recommended way to provide accessible names for input fields. By programmatically associating descriptive text with a form control, typically through the for attribute pointing to the input’s id, it ensures users of assistive technology clearly understand what information is required. Proper labels also improve usability by increasing the clickable area, since clicking the label sets focus to the input.

<label> element, used for about one-third of inputs (34.27% on desktop and 34.57% on mobile), followed closely by placeholder text (24.49% on desktop and 25.12% on mobile) and inputs with no accessible name at all (24.65% on desktop and 24.93% on mobile). Other sources, such as aria-label, title, or value attributes, and aria-labelledby relationships, account for only a small fraction of inputs.In 2025, about 35% of mobile inputs receive their accessible names from <label>, up from 32% in 2024. This is a positive trend.

We also saw a modest 2% reduction in inputs deriving accessible names only from placeholder text. Placeholder text is less reliable and not a substitute for labels. However, the proportion of inputs lacking accessible names altogether remained unchanged from last year, indicating ongoing accessibility gaps.

The 2025 data shows incremental improvement in label usage. It also underscores the need to continue expanding proper labeling practices to achieve full accessibility compliance and usability.

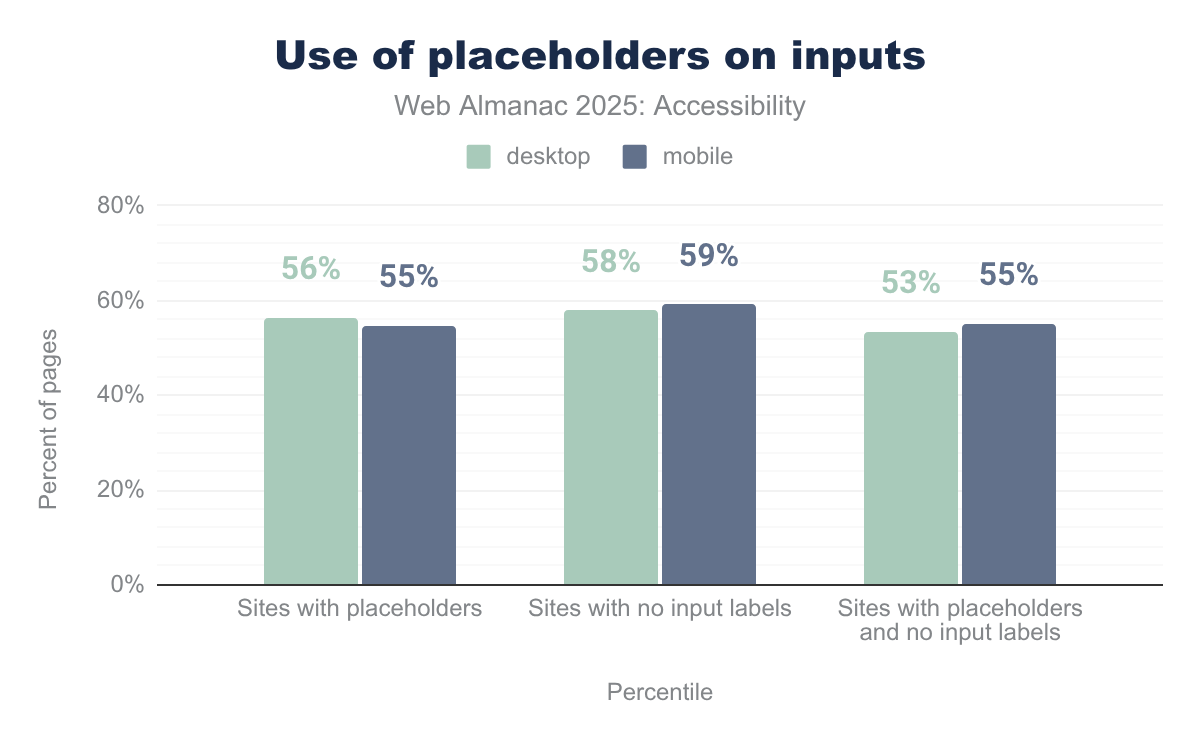

placeholder attribute

The placeholder attribute provides a hint or example of the expected input format inside a form field. But it should never replace the <label> element as the accessible name for that input. Placeholder text disappears as soon as the user starts typing, making it unavailable for reference.

Placeholder text also usually has poor default contrast, often failing WCAG color contrast requirements. Screen reader support for placeholders varies widely as well.

The recommended approach is to use visible, programmatically associated labels for inputs, with the placeholder serving only as a supplementary hint or example.

In 2025, there was a 2% reduction in the use of placeholder text as the only accessible name for inputs. Despite this positive trend, the practice remains all too common. 53% of desktop and 55% of mobile inputs rely solely on placeholder text for accessible naming, which still poses significant accessibility barriers.

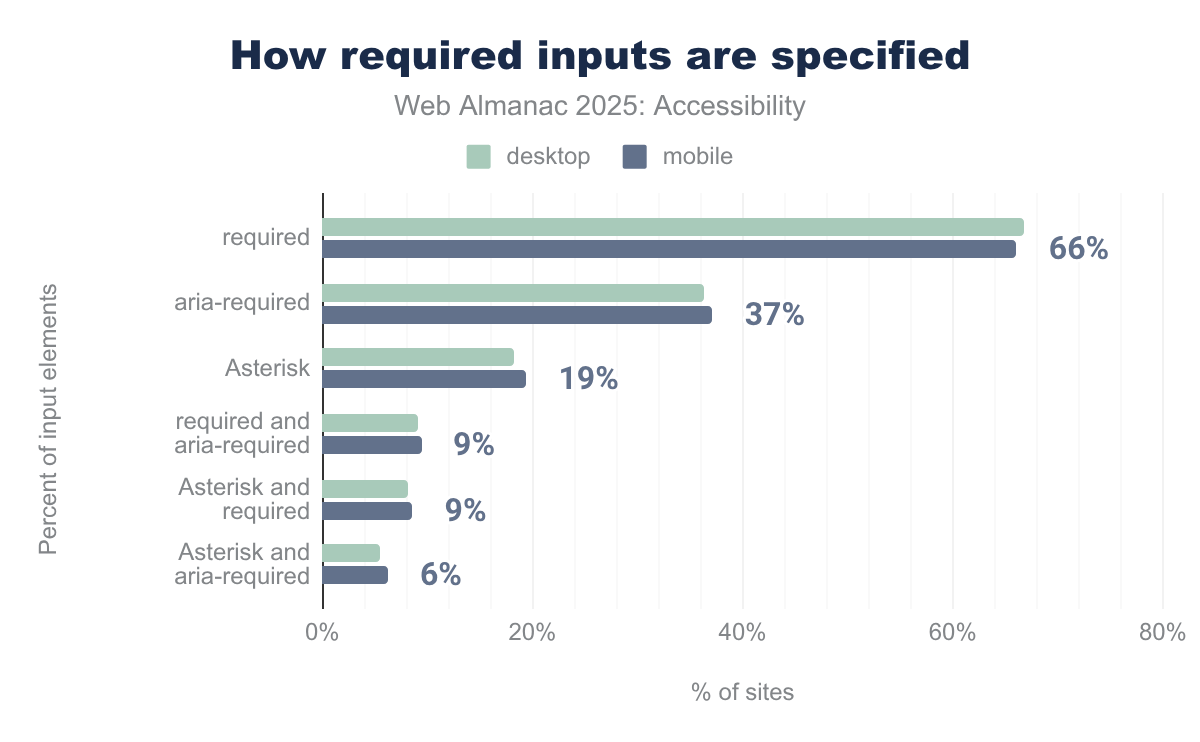

Requiring information

Communicating that a form field is mandatory is essential for usability and accessibility. While a visual indicator such as an asterisk (*) is common, it alone is insufficient because it lacks semantic information.

The HTML5 required attribute provides a native, machine-readable way to indicate that a user must fill in a field before submitting the form. This attribute works with many input types like text, email, password, date, checkbox, and radio. Browsers enforce validation and assistive technologies convey the required status to users.

required attribute is most common at 67% on desktop and 66% on mobile, followed by aria-required at 36% and 37%. Visual asterisks appear on 18% of desktop and 19% of mobile sites, with overlaps like both required and aria-required on 9% of sites for both platforms.We are seeing a modest increase in the adoption of the required attribute, up 1% in 2025 to 66% for mobile. Use of aria-required has dropped 3% to 37% for mobile. This indicates a gradual shift towards more semantic usage of native HTML validation over ARIA, which is intended to supplement but not replace native semantics.

Progress in 2025 reflects slow but steady movement toward better semantic indication of required inputs, improving form accessibility and user experience.

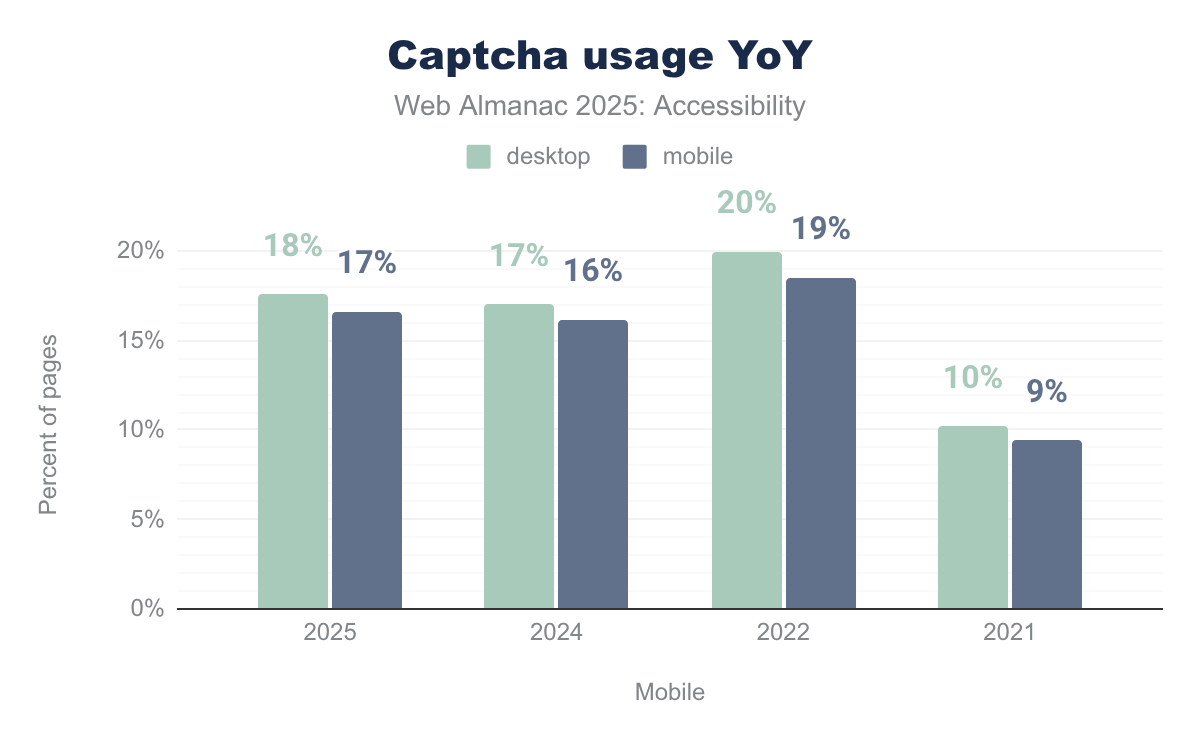

Captchas

CAPTCHAs differentiate humans from automated bots, mitigating malicious activity. The acronym stands for “Completely Automated Public Turing Test to Tell Computers and Humans Apart.” While CAPTCHAs serve a necessary security function, they frequently create significant accessibility barriers, particularly for people with visual, motor, or cognitive disabilities.

Traditional visual CAPTCHAs can be difficult or impossible for users with disabilities to solve. The W3C recommends exploring alternative verification methods that are more inclusive, such as:

- Audio CAPTCHAs that provide spoken challenges

- “Invisible” CAPTCHAs that work in the background without user input

- Incorporating multi-factor authentication methods or simpler verification flows.

In 2025, CAPTCHA use has remained roughly steady compared to previous years.

Notably, the Government of Luxembourg released a CAPTCHA scanner tool. It assesses and monitors CAPTCHA implementations across government websites, aiming to improve accessibility compliance in the public sector.

Continued efforts to replace or supplement visual CAPTCHAs with more accessible options are essential. All users should be able to complete verification steps without undue difficulty or exclusion.

Media on the web

Accessible media on the web requires providing alternative formats to ensure content is usable by everyone. Users with visual impairments benefit from audio descriptions that convey important visual information. Users who are deaf or hard of hearing rely on captions or sign language interpretation to access audio content.

Audio descriptions and captions aren’t enough. Transcripts are necessary for audio-only and video-only content, offering a complete textual alternative. For non-text content like images, provide appropriate alternative text. If they don’t add meaningful information, mark them as decorative.

The principles and requirements for accessible media remain consistent between 2024 and 2025, emphasizing the ongoing importance of providing inclusive multimedia experiences to users with disabilities.

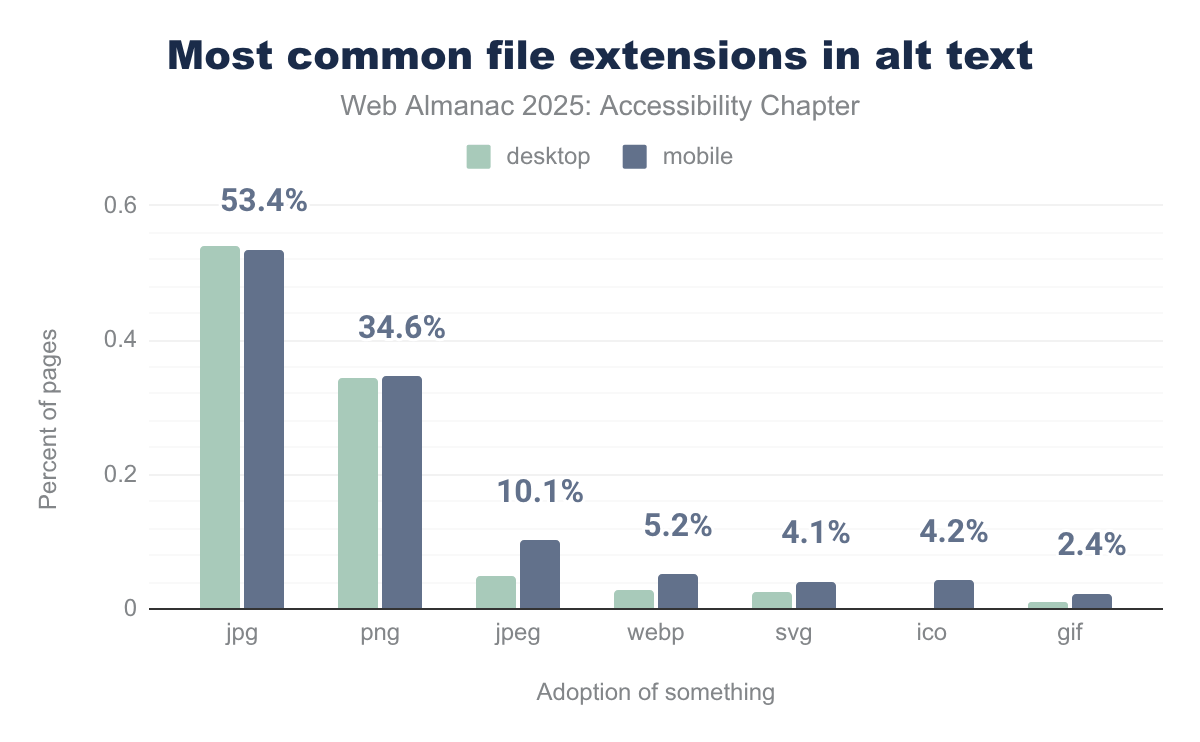

Images

The alt attribute provides a textual description of an image. It’s essential for screen reader users to understand the visual content. In 2025, this attribute remains fundamental to image accessibility, with no significant change in error rates from previous years.

alt text.

JPG and PNG files continue to dominate web images, but there is encouraging growth in the use of WEBP and SVG formats. SVG files offer rich semantics that benefit complex and interactive images.

jpg at 54.0% on desktop and 53.4% on mobile, followed by png at 34.5% and 34.6%. Other formats like jpeg (4.8% desktop, 10.1% mobile), webp, svg, ico, and gif make up smaller shares.alt text.

However, we noticed one issue that continues to persist: approximately 8.5% of image alt texts end with common file extensions like .jpg or .png. This typically happens when automated authoring tools insert filenames as alt text. Unfortunately, this adds no value and doesn’t help users relying on assistive technologies.

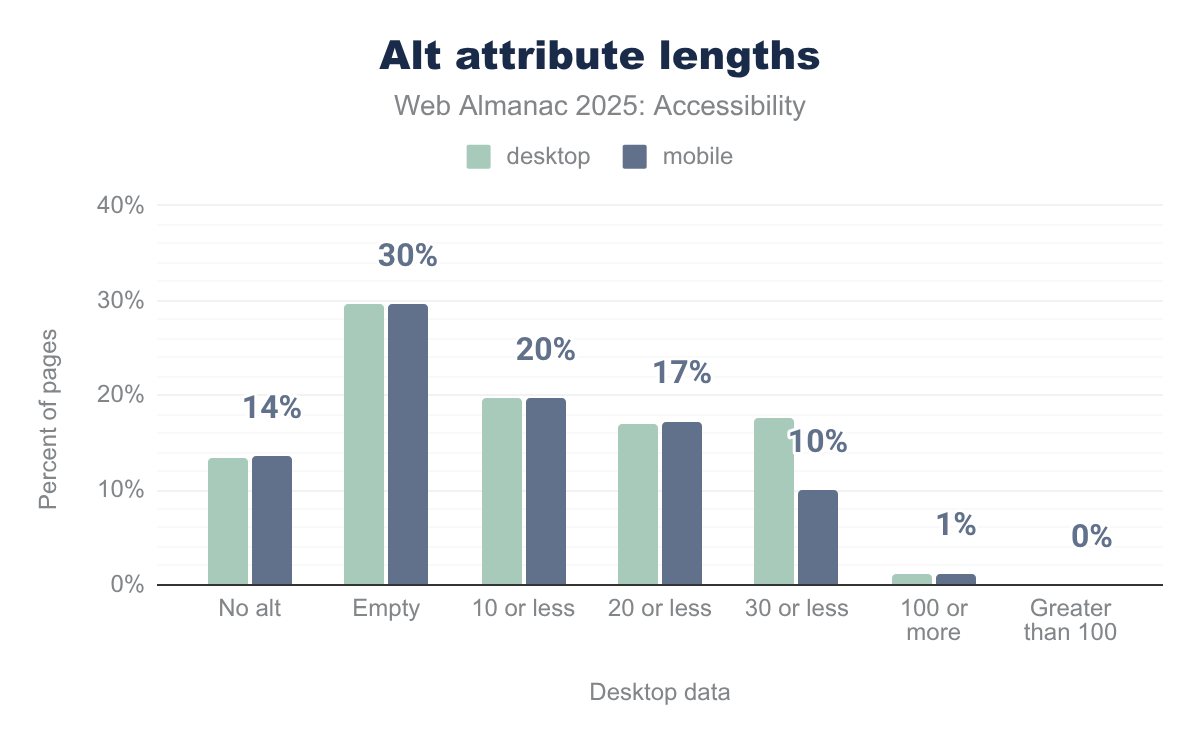

alt attribute lengths for images on desktop and mobile. Around 13–14% of images have no alt attribute and 30% use an empty alt on both platforms. Of the remaining images with non-empty text, most are short: about 20% have 10 or fewer characters, 17% have 20 or fewer, and 18% (desktop) and 10% (mobile) have 30 or fewer, while only about 1% have 100 or more characters and virtually none exceed 100 characters.alt attribute lengths.

There is a positive trend toward alt texts between 20 and 30 characters in length, which tend to balance descriptiveness and brevity. But about 50% of images still have either empty alt attributes or text shorter than 10 characters. Empty alt text is appropriate only for purely decorative images. Most images however convey important information deserving meaningful descriptions and therefore will benefit from a meaningful alt text.

Best practices continue to emphasize providing concise yet descriptive alt text tailored to image context, avoiding filenames, and using semantic file formats like SVG when appropriate. Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools show promise too. Drupal’s integration of AI-assisted alt text suggestions helps authors create better alt attributes by providing editable examples. Brian Teeman wrote an interesting critique of the AI generation of Alt Text.

Images remain an area with opportunities for significant accessibility improvement despite steady progress.

Audio and video

The HTML <track> element provides timed text tracks like captions, subtitles, and audio descriptions for media elements like <video> and <audio>. In 2025, this element is still underutilized. Despite its importance for users who are deaf, hard of hearing, or blind, adoption rates stay exceptionally low, at under 1%.

Many modern video platforms now commonly use HTTP Live Streaming (HLS) instead of the native <track> element. This may contribute to the low usage statistics. HLS, which requires custom implementation, means that developers need to be more intentional about building in caption support themselves. This means there’s more room for developers to forget about captions or do them poorly.

Captions are essential for deaf and hard of hearing users. They also benefit viewers in noisy environments or those with difficulty understanding spoken language. Audio descriptions enable users with visual impairments to gain context about visual content.

Compared to 2024, we’ve seen no significant growth in <track> usage for captions and subtitles, going from 0.1% to 0.4% on desktop and 0.1% to 0.2% on mobile. This tells us that the industry still has substantial room for improvement.

Assistive technology with ARIA

Accessible Rich Internet Applications (ARIA) is a set of HTML attributes to improve the accessibility of web content. ARIA is particularly valuable for complex or custom components that can’t be made accessible with native HTML alone. ARIA enhances dynamic, interactive user interfaces, making sure people using screen readers or other assistive technologies can understand and interact with all page elements.

ARIA must be used with care.

Incorrect or excessive use can introduce new barriers, causing confusion for both users and accessibility tools. For example, ARIA attributes that don’t match the intended functionality, roles added to inappropriate elements, or redundant ARIA can disrupt the user experience and increase accessibility errors.

Adrian Roselli’s work highlights the limitations of certain ARIA properties, such as aria-description, and underscores the importance of understanding both the strengths and pitfalls of ARIA.

The most important principle for ARIA is:

If you can use native HTML, you should.

Native elements like <button> , <input>, and <nav> come with built-in accessibility that ARIA can’t fully reproduce. ARIA should only supplement native semantics where required, not replace them.

Recent guidance by experts including Florian Schroiff as well as current best practices reinforce applying ARIA only for complex custom elements, and strictly following specifications to avoid accidental exclusion or miscommunication.

In 2025, ARIA continues to play a vital but occasionally problematic role in web accessibility.

ARIA roles

ARIA roles communicate an element’s purpose or type to assistive technologies. In 2025, they continue to play a significant role in making web content accessible. While native HTML elements like <button> come with built-in semantics, ARIA provides the ability to assign roles to custom components that lack native equivalents, such as tabbed interfaces or dialog components.

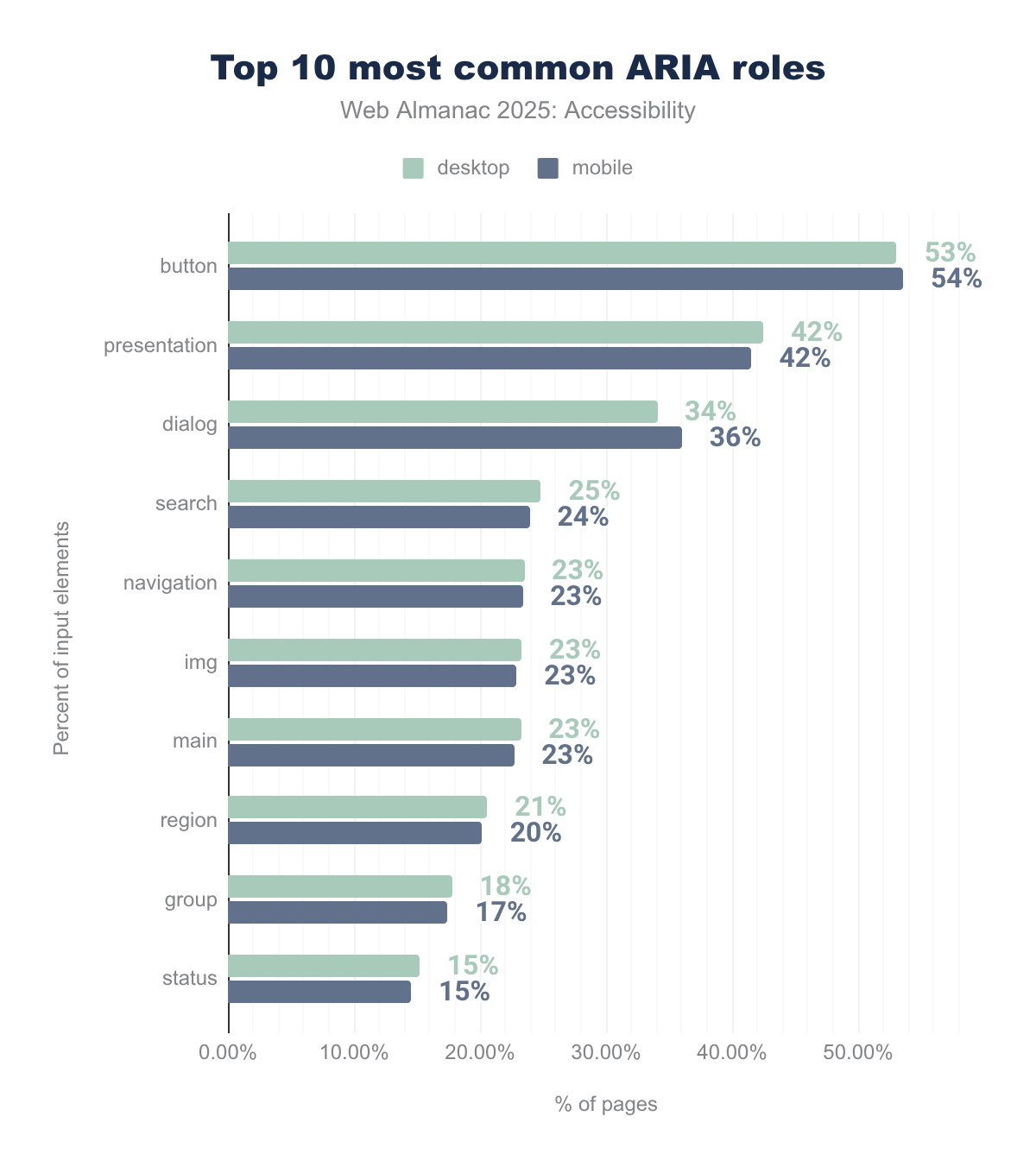

button is the most widely used role (53.06% on desktop and 53.56% on mobile), followed by presentation (42.48% and 41.54%) and dialog (34.05% and 36.01%). Other frequently used roles include search, navigation, img, main, region, group, and status, all appearing on roughly 15–25% of pages.We’ve seen an approximately 4% increase in the use of the ARIA button role, reaching 53% on desktop and 54% on mobile sites in 2025. We’ve seen similar increases in the use of roles like presentation and dialog, whereas the use of the search role usage remains stable.

The increased use of the ARIA button role raises concerns. It often indicates that websites are applying roles like button to non-semantic elements such as <div> or <span>. Or they’re redundantly assigning roles to native HTML elements like <button>.

Using the presentation role

Applying role="presentation" or role="none" instructs assistive technologies to treat the element as purely presentational. It removes its native semantics from the accessibility tree. While this can be useful for layout elements that convey no meaningful information, overuse or misuse can create significant accessibility barriers.

For example, applying role="presentation" to a <ul> element causes the entire list semantics, including those of child <li> elements, to be ignored. Screen reader users lose crucial contextual and structural information, like how many items are in a list.

While the presentation role can help remove misleading semantics when elements are used purely decoratively or for layout, it should be applied sparingly and with clear intent.

presentation role.

In 2025, the use of role="presentation" increased by 2%, continuing a concerning trend.

Labeling elements with ARIA

Browsers maintain an accessibility tree that exposes information about page elements, such as their accessible names, roles, states, and descriptions. Assistive technologies rely on this to convey context to users. An element’s accessible name is crucial and is usually derived from visible text content. However, ARIA attributes like aria-label and aria-labelledby can be used to explicitly set or override accessible names when native text is insufficient or unavailable.

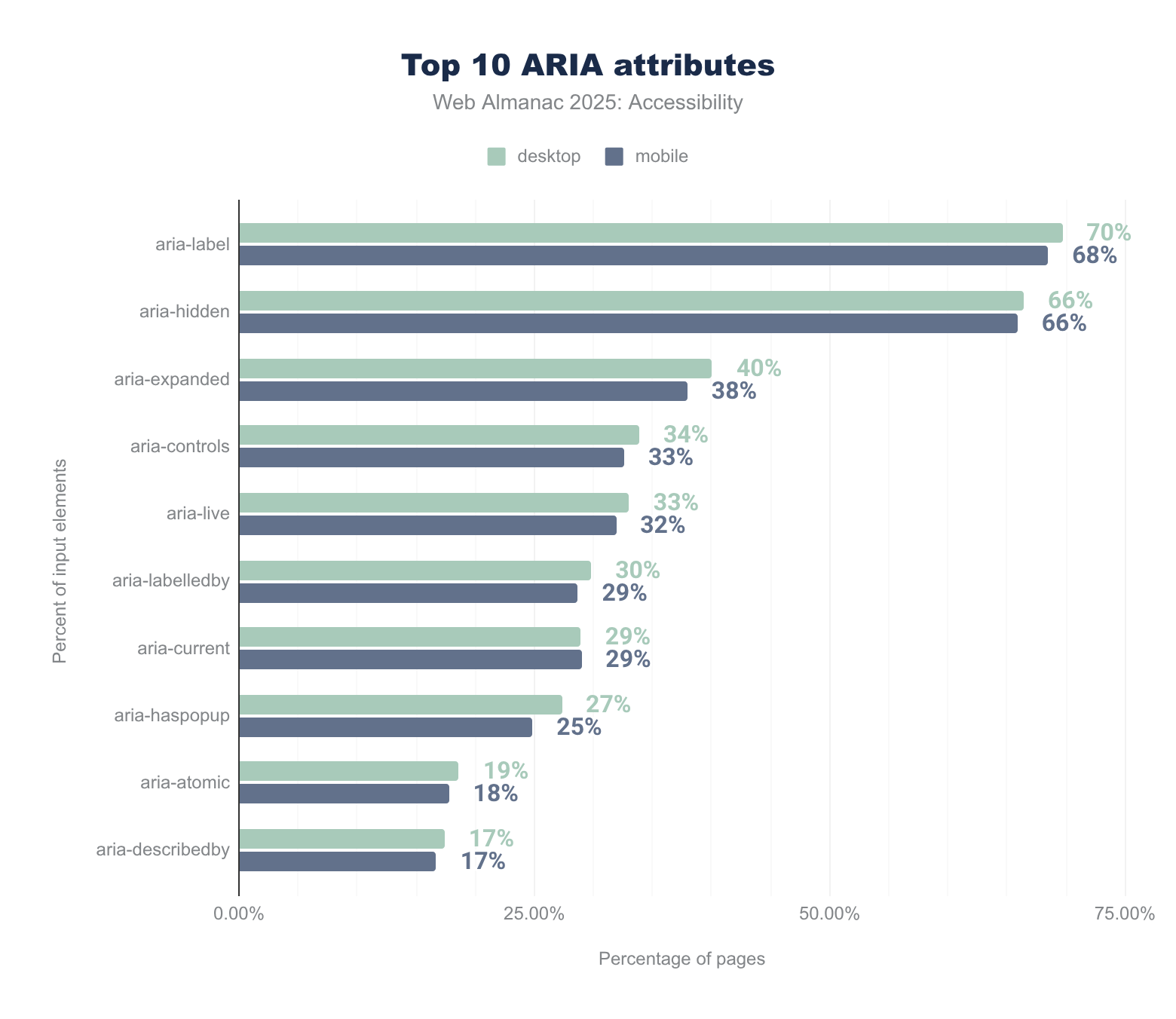

aria-label leads at 70% on desktop and 68% on mobile, followed closely by aria-hidden (66% on both). Other frequently used attributes include aria-expanded (40% and 38%), aria-controls (34% and 33%), aria-live (33% and 32%), and aria-labelledby (30% and 29%), with usage decreasing down to aria-describedby at 17% on both desktop and mobile.In 2025, the use of almost all top ARIA attributes increased. Desktop usage of aria-label rose by 5% and aria-labelledby by 3%. Use of aria-describedby on desktop decreased by 1%.

These changes suggest developers increasingly assign accessible names programmatically to more elements. This can be helpful but also problematic if not carefully implemented.

aria-label attributes (28% and 29%). About 9% of desktop buttons and 11% of mobile buttons have no accessible name, with smaller shares from title (1%) and value (5% and 4%) attributes.We are seeing a concerning trend with the continued increase of 4% to 5% in defining buttons with aria-label alone, without corresponding visible labels. This disconnect between what a user sees visually and what assistive technologies announce can create confusion and barriers. This is especially true for people with cognitive disabilities or who use voice input. Ideally, the accessible name and visible label should match to provide a consistent user experience.

Nearly 66% of pages use the aria-label attribute, up from earlier years, making it the most frequently used ARIA attribute for accessible names. About a quarter of pages use aria-labelledby.

While using ARIA to enhance accessibility is positive, it underscores the importance of testing with assistive technologies and involving users with disabilities to ensure meaningful and accurate naming.

Hiding content

The aria-hidden="true" attribute removes an element and all its descendants from the accessibility tree, making the content invisible to screen readers. This is useful for hiding purely decorative or redundant visual elements that would otherwise confuse non-visual users.

aria-hidden attribute.

In 2025, use of aria-hidden increased by 3% compared to 2024. Approximately 66% of websites have some content hidden using this ARIA attribute.

Similarly, the aria-expanded attribute, which signals whether a section of content is expanded or collapsed, also saw increased adoption, reaching 40% of desktop sites and 38% of mobile sites. This attribute is important for communicating the state of disclosure widgets like accordions or expandable menus to assistive technologies.

Thoughtful application of these ARIA attributes remains crucial in 2025. They help with the management of dynamic content and ensure inclusive experiences across devices and user needs.

Screen reader-only text

In 2025, a common and effective technique for accessibility is the use of screen reader-only text. This is text that’s visually hidden but remains accessible to assistive technologies like screen readers. This approach is often applied to provide additional context, instructions, or descriptive labels for interactive elements without cluttering the visible interface.

Developers frequently use common CSS classes such as .sr-only, .visually-hidden , or .element-invisible to achieve this effect. These classes typically use off-screen positioning, clipping, or zero-sized boxes to hide the text visually while ensuring it remains in the accessibility tree and readable by screen readers.

Usage of these common screen reader-only classes remained essentially unchanged between 2024 and 2025. Some websites include hidden text to provide context to screen reader users in ways that may not be apparent from the semantic HTML alone.

Dynamically-rendered content

ARIA live regions are critical for making dynamically changing content accessible. They inform screen readers about updates to page content, such as form validation messages, status updates, or live feeds. These updates occur without a full page reload, and are therefore necessary for users to receive important information without disruption.

| Role | Desktop | Mobile | Implicit aria-live value |

|---|---|---|---|

| status | 15.18% | 14.51% | polite |

| alert | 7.12% | 6.74% | assertive |

| timer | 0.91% | 0.84% | off |

| log | 0.61% | 0.55% | polite |

| marquee | 0.09% | 0.10% | off |

aria-live value.

In 2025, about 33% of sites use the aria-live attribute, up 4% from 2024. Usage of the role value status, essentially an aria-live value of polite, increased by approximately 5%. This signals more widespread adoption of polite notifications that inform users of non-urgent updates.

Additional ARIA roles, such as alert, timer, log, and marquee, also have implicit aria-live attributes with predefined behaviors, enabling a broad spectrum of live region use cases.

Increased use of ARIA live regions in 2025 reflects progress in communicating dynamic content updates effectively, supporting users who rely on assistive technologies to interact with modern, responsive web experiences.

User personalization widgets and overlay remediation

Accessibility widgets and overlay remediation tools are third-party scripts designed to enhance website accessibility. They offer user personalization options, such as font size or contrast adjustments, and automated fixes for common accessibility issues.

These overlays often promise quick-fix compliance but fall short of addressing complex accessibility challenges that require manual code and design changes. The European Disability Forum has warned that such tools can interfere with users’ own assistive technologies, creating conflicts that reduce accessibility and frustrate users.

Though overlays can help remove some surface-level barriers and provide additional personalization features, reliance on them often leads organizations to stop investing in proper accessibility. Overlays generally have more usability, security, and performance drawbacks than fixing underlying code issues.

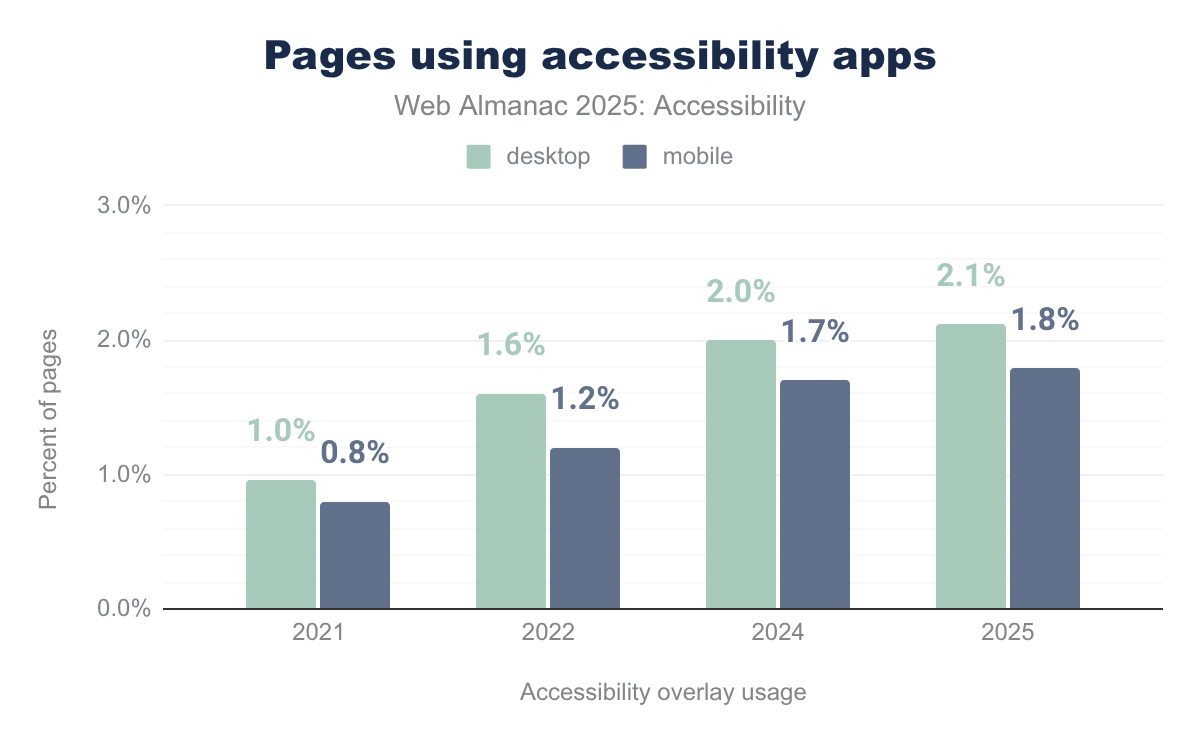

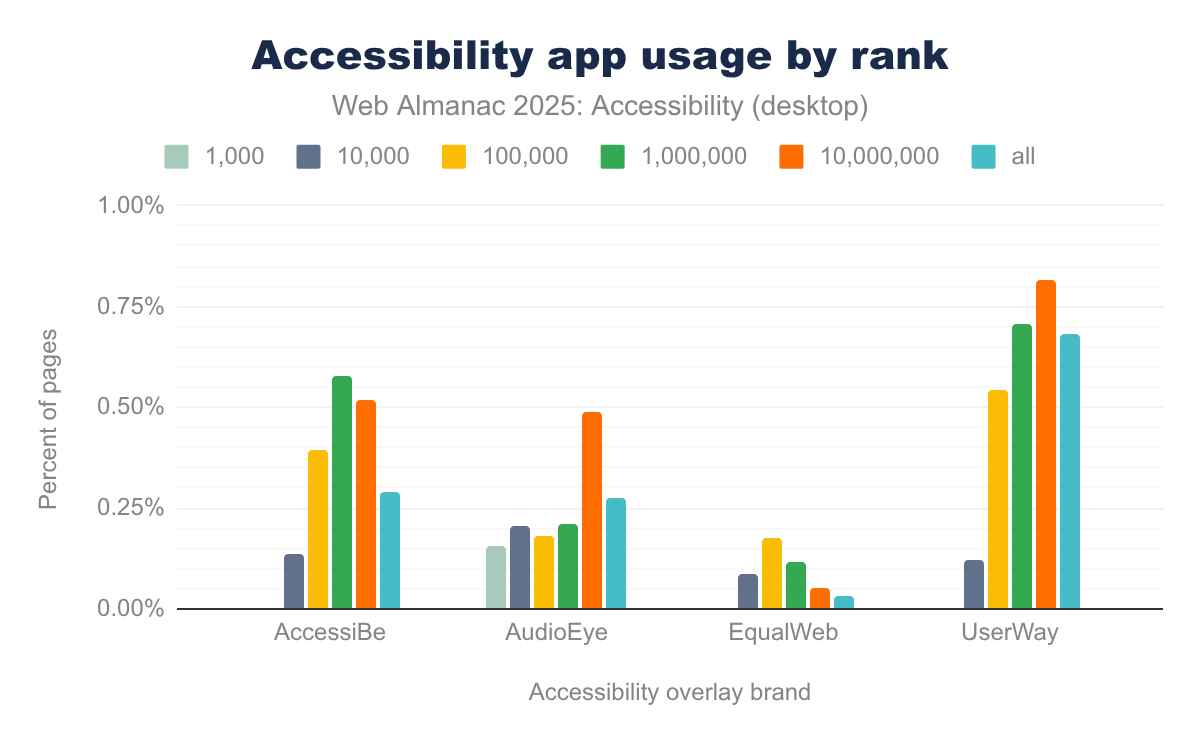

Data shows about 2% of desktop sites use such accessibility apps. Rates are even lower rates among the highest-traffic sites, at 0.2% among the top 1,000. This pattern shows that overlays are mostly adopted by lower-traffic sites and remain a controversial and imperfect solution.

Despite a marginal increase in their use in 2025, the distribution of these accessibility apps remains consistent with 2024, dominated by providers like UserWay, AccessiBe, AudioEye, and EqualWeb.

Confusion on overlays

Accessibility overlays and personalization widgets, while growing marginally in use by about 2% in 2025, continue to be a source of significant controversy and confusion.

Leading organizations such as the International Association of Accessibility Professionals (IAAP) and the European Disability Forum (EDF) have explicitly warned that overlays are not a silver bullet. They must never impede users’ access or interfere with their assistive technologies and shouldn’t be marketed as making a site fully compliant.

Marketing claims often create unrealistic expectations among organizations, leading to legal and practical risks. These tools can’t replace inclusive design, manual accessibility testing, and ongoing remediation. All these are essential to meet accessibility standards.

The European Accessibility Act and other regulations emphasize that accessibility must be built into websites at the source. While accessibility overlays exist, they don’t meet the detailed criteria of accessibility standards if the underlying website itself isn’t accessible. They’re therefore not an appropriate solution on their own.

Bitvtest.de has recently decided to stop testing and disallow their certification mark on websites that use an overlay tool. Bitvtest is a professional accessibility testing service built around the German BITV-Test, which is a structured way to check how accessible a website or app is.

The Impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a broad field of computer science focused on building systems that can perform tasks that normally require human intelligence. Within this field, large language models (LLMs) are a specific kind of AI system trained on very large datasets to learn statistical patterns.

LLMs use these patterns to generate and transform text, answer questions, and follow instructions, but they don’t have understanding or intent in a human sense. They predict likely words and sentences based on their training data.

Web accessibility tools increasingly rely on LLMs. Many platforms now offer AI-generated alt text as a way to address missing image descriptions, though the quality and accuracy of these automated solutions varies widely.

Developers are adding AI tools, like GitHub’s Accessibility Scanner, to their every day work. These tools give instant feedback and accessibility recommendations, making it easier to fix accessibility issues.

But AI in accessibility isn’t without its problems.

Right now, there’s no standard way to tell if AI made or improved a website or its content. This makes it harder to evaluate sites and leaves users in the dark about what they’re looking at.

Some experts, like accessibility advocate Léonie Watson, talk about an “agentic web” where AI changes how we interact with content online. This raises questions about how accessibility standards need to adapt.

AI-powered browsers and extensions are becoming mainstream fast. Voice assistants and AI agents built into browsers might soon handle most of our basic information searches. People already have the option of choosing AI-generated answers over traditional search results. This shift could help or hurt accessible design. It all depends on whether these AI tools are themselves fully accessible.

Experts like Joe Dolson have explored whether AI can build fully accessible websites on its own, highlighting both the potential and current limitations of the technology. Scott Vinkle’s experiences at Shopify shows how AI can improve accessibility in real-world situations.

The A11Y Collective blog on Artificial Intelligence and Accessibility points out that while AI tools that automate alt text or real-time captions, and voice assistants can help accessibility at scale, they still struggle with accuracy, context, privacy, and bias.

Research by Dries Buytaert shows AI can tackle huge backlogs of unlabeled images, but human review is still essential for quality. He explores the balance between quality, privacy, cost, and complexity for organizations considering AI-powered alt text.

Digital Accessibility Training outlines the opportunities and challenges of AI for content creators. AI tools enable accessibility features at scale but raise concerns about content validity, bias, and ethical usage.

Hidde de Vries contrasts how humans and language models approach accessible component code. Humans base HTML, CSS, and ARIA decisions on specifications, user needs, assistive technology behavior, and platform quirks, all guided by intentions for the interface. LLMs instead predict likely code from training data, which is problematic because most existing code has accessibility issues, and the models lack intent or understanding of specific users.

Adrian Roselli acknowledges that recent advances in computer vision and LLMs have brought real benefits, such as better image descriptions and improved captions and summaries. However, he argues these tools still lack context and authorship. They can’t know why content was created, what a joke or meme depends on, or how an interface is meant to work. Their descriptions and code suggestions can easily miss the point or mislead users.

AI raises significant ethical concerns that go beyond accessibility.

One major issue is environmental impact. A study on carbon emissions and large neural network training estimated that training a single large language model such as GPT‑3 consumed more than 1,200 megawatt-hours of electricity and produced around 500–550 metric tons of CO₂-equivalent. This is comparable to the lifetime emissions of over 100 gasoline cars. For more information refer to the Sustainability chapter.

Another core concern is how training data is collected and used. Several high-profile lawsuits allege that AI vendors scraped and used copyrighted material without permission or compensation. This included millions of stock photos and books.

Studies of large models show they can amplify ableist, racist, and other harmful biases present in their training data. This ultimately shapes how disability, race, and gender are described, reinforcing stigma at scale.

Looking forward, it’s clear to us that AI will increasingly become a tool web developers and content creators rely on. However, AI should support human expertise, not replace it.

As these tools get better, the accessibility community needs to answer some important questions in 2026 and beyond:

- How do we check if AI-generated content is accurate and accessible?

- What standards should govern AI use in web content?

- How will assistive technologies work with AI-driven interfaces?

- Can AI provide equal accessibility while respecting individual needs?

- What ethical guidelines do we need to prevent AI from reinforcing bias or excluding people?

Sectors and accessibility

This section compares accessibility scores across various industry and community sectors to identify patterns and leaders.

Country

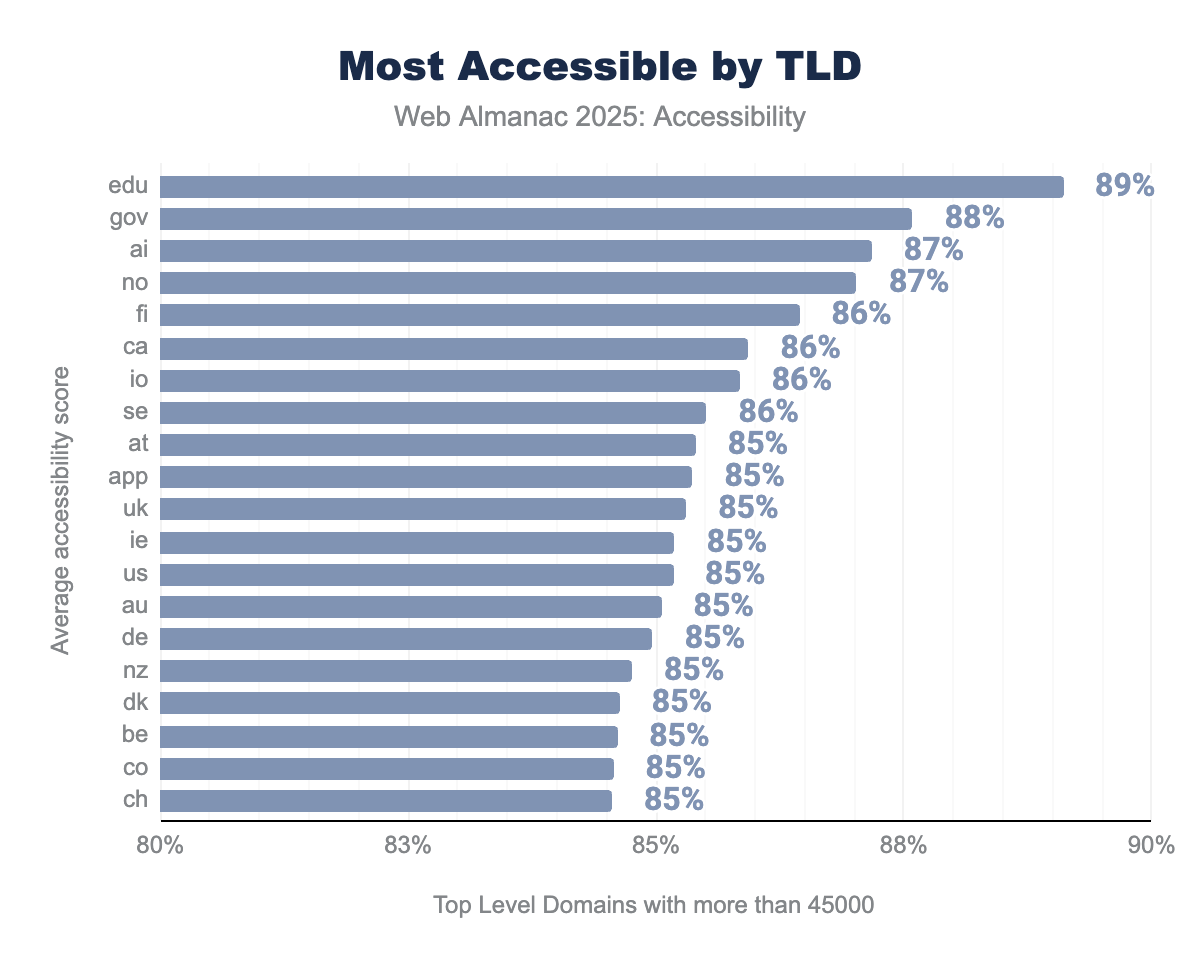

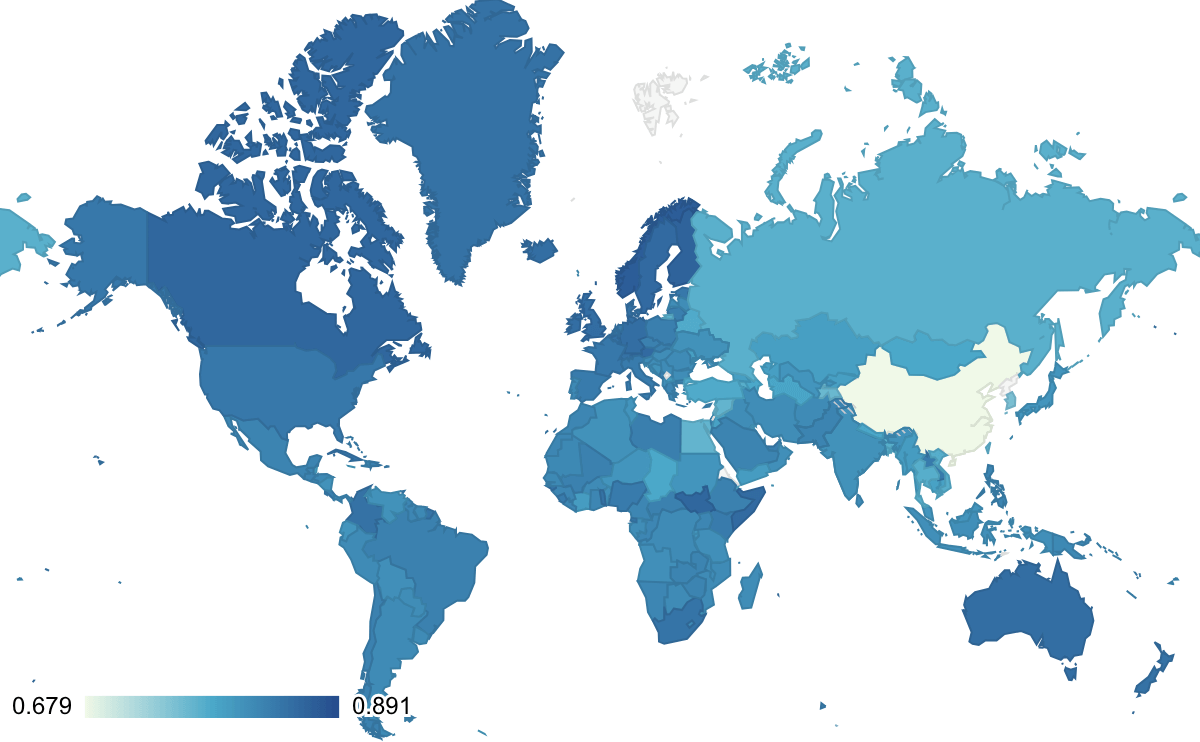

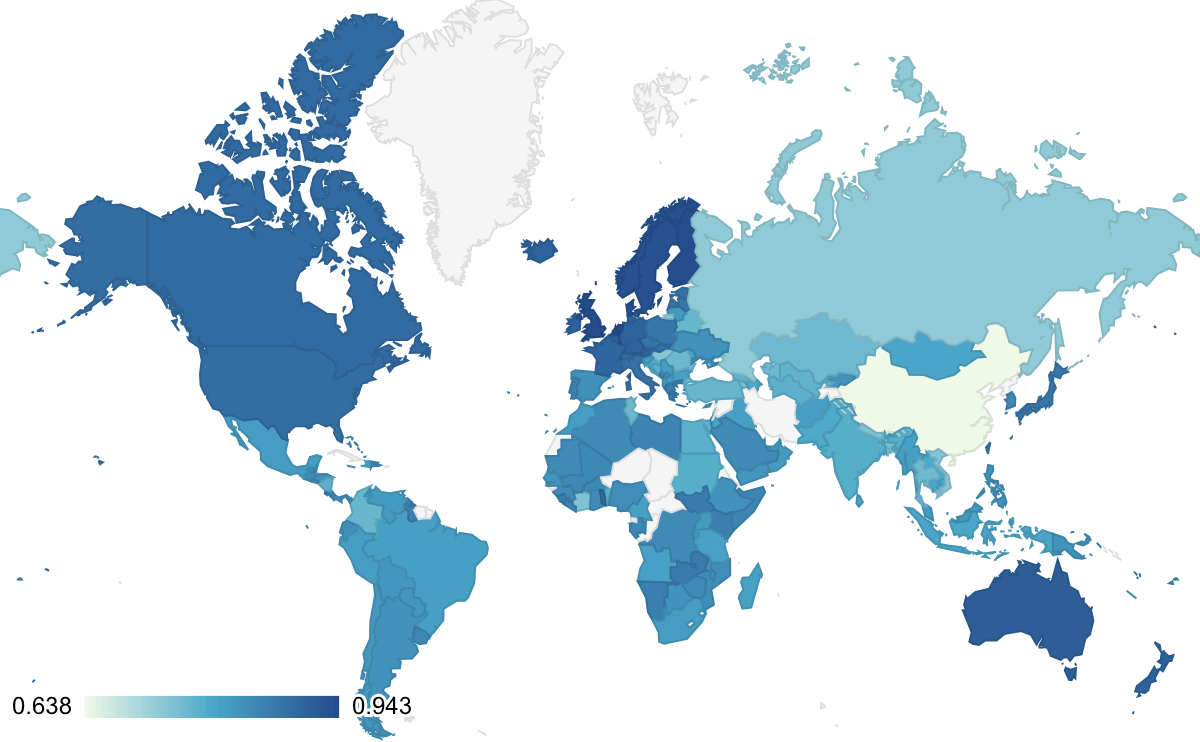

We can identify a website’s country of origin either by the server’s geographic location (GeoID) or by its Top-Level Domain (TLD). Both methods have limitations. Hosting costs, server location strategies, and domain ownership practices mean that a website’s server may not reflect its target audience. Globally-used TLDs like .ai or .io aren’t necessarily tied to their countries of origin.

In 2025, the United States remains the most accessible country by GeoID, a position driven by decades of Section 508 compliance requirements for federal agencies and ongoing ADA Title III litigation. The .edu and .gov TLDs also lead accessibility metrics, reflecting mandatory compliance for U.S. government and educational institutions.

We also note the EU Accessibility Act’s limited impact in 2025. While the Act became fully effective on June 28, 2025, mandating that private and public sector digital services be accessible across the European Union, preliminary data shows no dramatic spike in website accessibility for European-based sites.

This lag likely reflects implementation challenges, transitional periods for existing services, and the time required for organizations to redesign and audit their digital offerings.

Legal enforcement and the threat of litigation remain the strongest drivers of accessibility compliance, as evidenced by the United States’ leading position. The full impact of newer European and global legislation may take years to manifest in web accessibility statistics, as organizations work through implementation timelines and transition periods.

We noticed a notable trend emerging in 2025. .ai domains appeared for the first time in accessibility rankings, now outperforming all TLDs except .edu and .gov. This likely reflects the growing adoption of AI-related businesses, many of which prioritize modern development practices, including accessibility.

Originally assigned to Anguilla, a small Caribbean island, in 1995, the .aiTLD extension remained relatively obscure for nearly 15 years until 2009, when Anguilla opened direct registrations worldwide. The domain lay dormant for most of its history until the artificial intelligence boom of 2022 onward transformed it into one of the fastest-growing TLDs globally.

The catalyst came with the arrival of ChatGPT in late 2022, which sparked unprecedented interest in AI. Between July 2022 and July 2023, registered .ai domains skyrocketed from 75,314 to 196,292, a 161% increase in just twelve months.

Geographically, North America drives the majority of .ai registrations at 62.5%, with the United States alone accounting for 62.5% of all registered .ai domains. Asia follows at 18.8%, and Europe at 17.2%.

Many .ai domain holders are venture-backed, well-funded tech startups which are more likely to use AI. It’s still up for debate whether AI can produce more accessible code than human teams, but this is one indicator.

Unlike older traditional companies using .com or .org, newer AI companies often build with contemporary web standards and tools that consider accessibility from the start. These companies that use an .ai domain and sell AI products are very likely to have involved AI in building their website, at least by consulting it for code or content, if not by using it in more automated agentic setups.

Traditional TLDs like .com, .org, .net don’t rank as accessibility leaders. This suggests that domain type alone isn’t a strong predictor of accessibility compliance.

The map of TLD ranking is very similar to 2024, but obviously doesn’t include the increasing number of non-country specific TLDs now available.

Government

Government websites remain a critical arena for demonstrating public commitment to accessibility. But implementation varies dramatically across jurisdictions. The 2025 data reveals important trends in global government website accessibility, influenced by recent legislation, methodological changes in data collection, and enforcement mechanisms.

We used a different methodology this year to be able to assess a broader range of domains which fell outside of scans in 2024.

In 2024, we only sampled 79 domains from the government of the Netherlands. In 2025 we queried over 10 times that number with 957 domains. We similarly scanned about twice the number of domains for Luxembourg and Finland. The greater accuracy means we have a more comprehensive dataset, but also a more complex year-over-year comparison.

In the United Kingdom, we saw an improvement to 94% accessibility, up 2% from 2024. This reflects the benefits of standardized design systems, such as the UK Government’s Digital Service Standard, which prioritizes accessibility across all public digital services. The Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Finland continue to lead, with the Netherlands achieving 98% in previous years. They have maintained this position through consistent governance frameworks and design system prioritization.

We also made an effort to include Scotland (gov.scot) and Wales (gov.wales). In 2025, we averaged from 19,568 domains, while in 2024 it was only 16,594.

Monitoring is a key part of prioritizing accessibility, and we applaud dashboards like the French Government’s which highlight progress on a number of website quality indicators, including accessibility. Much of the code behind this is open source. The Dutch government also has a dashboard that keeps track of almost 9.000 websites and applications. At the time of writing, 60% of all tracked web properties comply with legal requirements.

The Accessibility Monitoring Reports done by AccessibleEU are important, but much more abstracted. The Web Accessibility Directive in the EU requires member states to monitor and report accessibility compliance every 3 years. These reports are publicly available.

The European Union’s evolving regulatory landscape has significantly impacted government website accessibility in 2025.

The EU Web Accessibility Directive requires public sector organizations to meet specific technical standards. The broader European Accessibility Act (EAA), which became fully effective on June 28, 2025, extends requirements to private sector organizations in key sectors such as e-commerce, travel, and banking.

Despite this regulatory momentum, 2025 accessibility data shows no dramatic spike in European government website compliance, suggesting that implementation is still underway and the full impact may not be visible until 2026.

EU Member States are required to publish accessibility statements and provide feedback mechanisms for users to report barriers. Accessibility statements are an important part of the EU’s Web Accessibility Directive, but as yet, we don’t have a good way to include them in the site scans. The Funka Foundation has reminded us of the limitations of this type of testing for compliance.

The map of 2025 is almost indistinguishable from 2024.

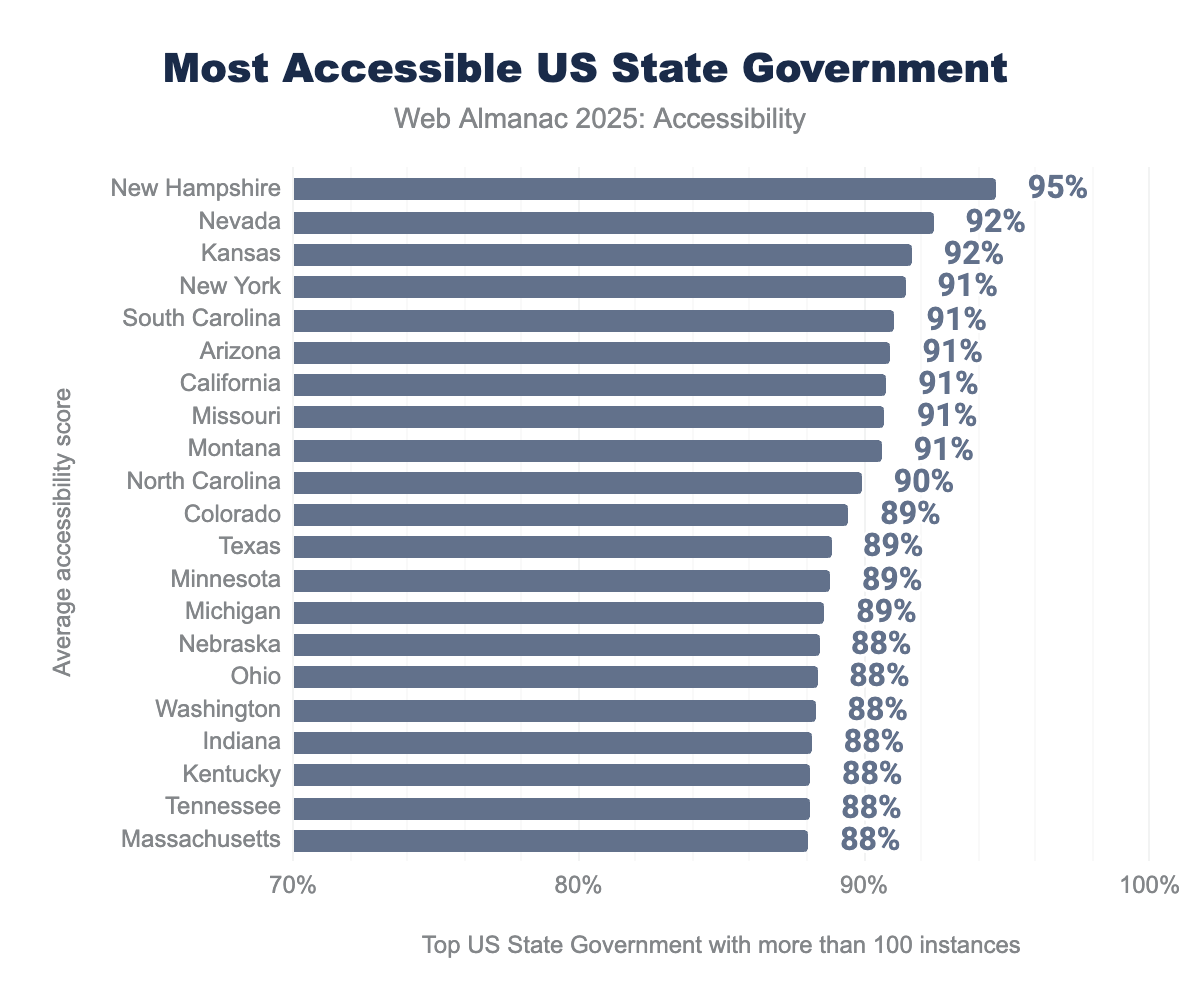

In the United States, state government compliance remains inconsistent despite new federal mandates. The Department of Justice’s (DOJ) final rule on Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act, published in June 2024, requires all state and local government entities to achieve WCAG 2.1 AA compliance by specific deadlines: April 26, 2026, for entities serving populations of 50,000 or more, and April 26, 2027, for smaller entities.

States like Colorado and Vermont have excelled by establishing centralized governance structures. Colorado’s Statewide Internet Portal Authority (SIPA) demonstrates how centralized management improves accessibility across multiple agencies.

Nevada, Kansas, California, and New York did well in the samples from both years. But the averages don’t indicate that state governments made any significant progress in achieving the new requirements from the 2024 US Department of Justice Final Rule to Strengthen Web and Mobile App Access. State technology leaders at the National Association of State Chief Information Officers (NASCIO) national conference reaffirmed accessibility as a top priority.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which turned 35 in July, was pioneering work that set a precedent globally.

Singapore’s recent commitment to accessibility improvement, demonstrated through the open source tool Oobee, shows emerging global momentum. Oobee allows organizations to scan hundreds of pages and generate consolidated accessibility reports, positioning it as a Digital Public Good.

Content Management Systems (CMS)

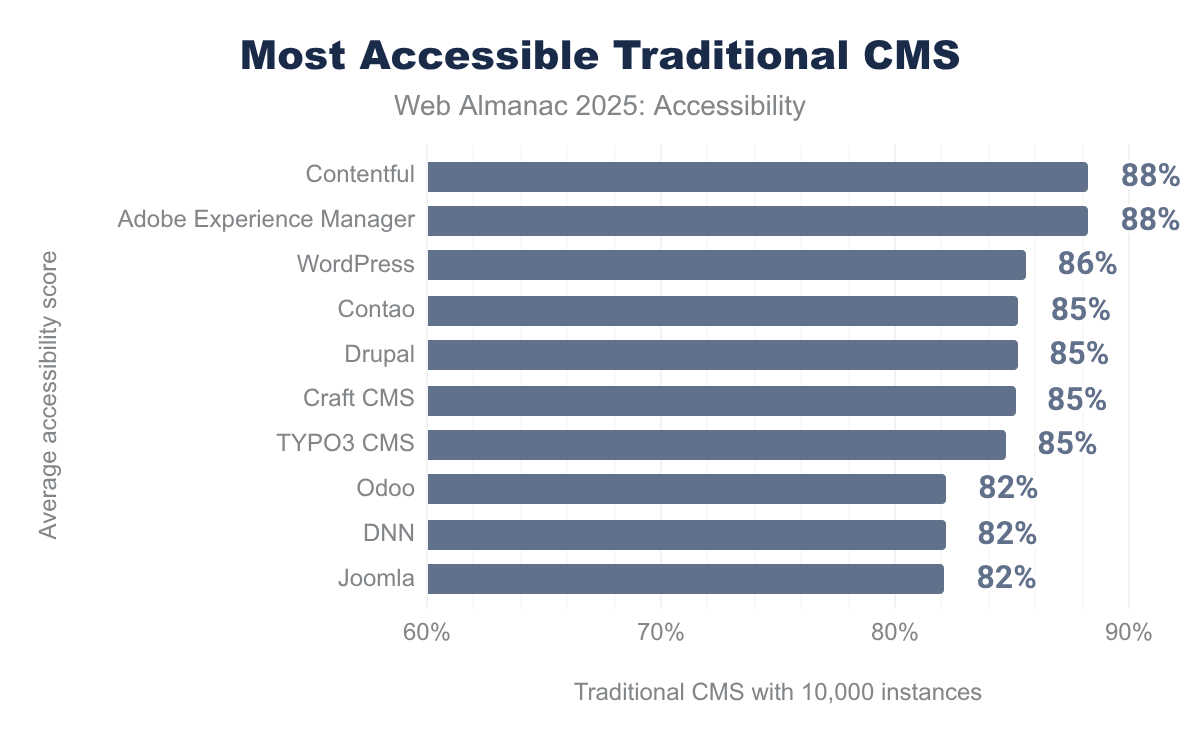

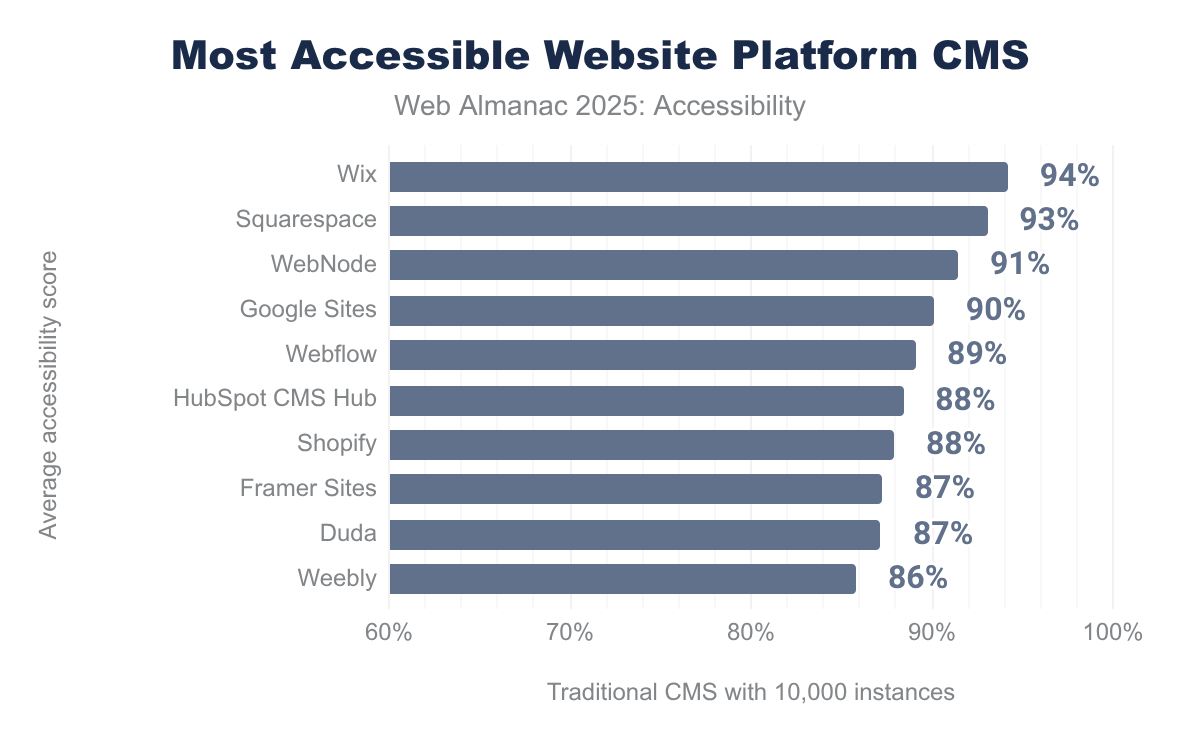

A website’s choice of Content Management System (CMS) significantly influences its accessibility outcomes. Using Wappalyzer data, the 2025 Web Almanac compared accessibility scores across traditional CMSs, platforms, and specialized website builders. This revealed both consistent patterns and notable outliers.

Among traditional CMSs, Sitecore maintained 85% accessibility in 2025, though its instance count dropped below 10,000. Adobe Experience Manager (AEM) and Contentful continue to lead, likely because larger corporations adopting these enterprise solutions have more resources to address accessibility issues. WordPress showed no significant improvement from 2024, but rose to third place, reflecting its market dominance and the growing accessibility consciousness of its user base.

Remarkably, the top five traditional CMSs share consistent error patterns. Color contrast, link names, and heading order dominate as the most common issues. These errors primarily reflect content choices rather than platform limitations, since a CMS can’t dictate link naming or color selections. However, AEM stands alone with label-content-name-mismatch in its top-five errors. WordPress is unique in having meta-viewport errors.

In the top 10 CMS, only DNN has image-alt in the top 3 errors. For most traditional CMSs, image-alt and target-size are consistently in the fourth or fifth place for Google Lighthouse errors.

| Platform CMS | Most popular | Second most | Third most | Fourth most | Fifth most |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wix | heading-order | link-name | color-contrast | button-name | target-size |

| Squarespace | color-contrast | heading-order | link-name | label-content-name-mismatch | frame-title |

| Webnode | heading-order | link-name | frame-title | color-contrast | image-redundant-alt |

| Google Sites | image-alt | link-name | aria-allowed-attr | heading-order | color-contrast |

| Webflow | link-name | color-contrast | heading-order | html-has-lang | target-size |

Website platforms like Wix, Squarespace, and Google Sites significantly outperform traditional CMSs in accessibility. This superior performance likely stems from their approach. These platforms often constrain user choices through templated designs and built-in accessibility defaults, reducing opportunities for poor accessibility decisions.

The data proves that CMS choice meaningfully impacts accessibility outcomes, even when content creators must take final responsibility for some decisions. Platforms with stricter design constraints and embedded accessibility defaults perform better, while those offering maximum flexibility leave accessibility decisions to users.

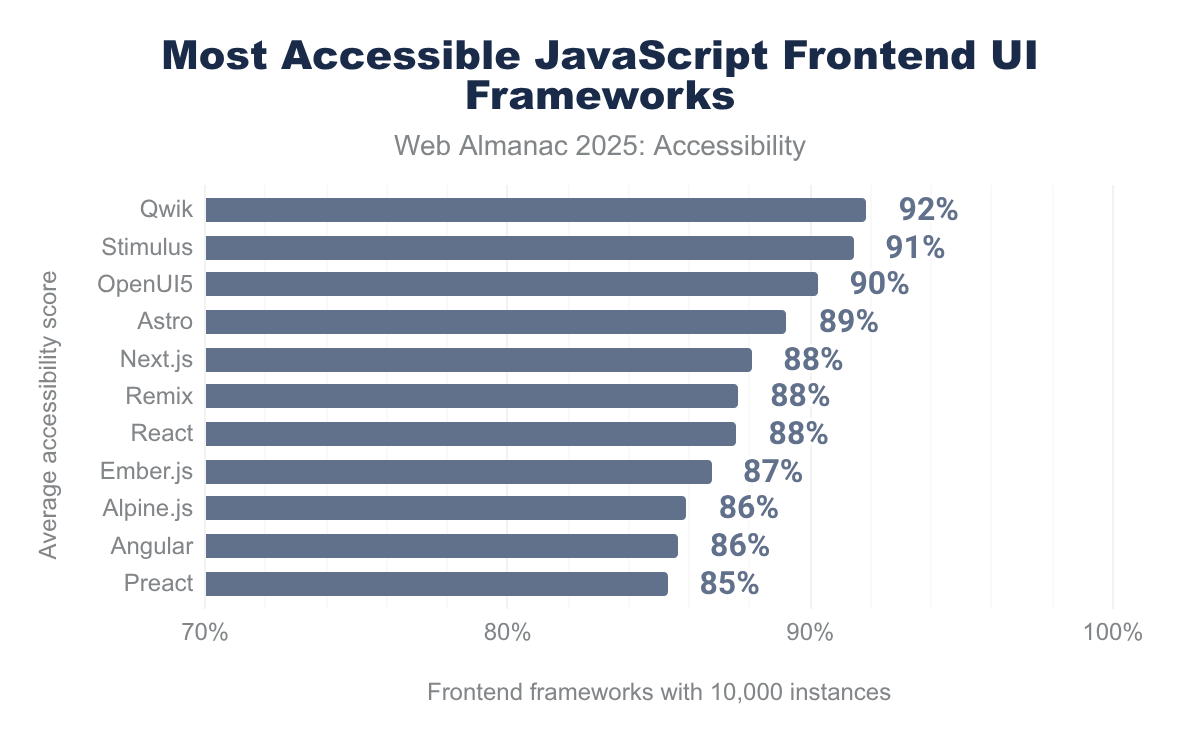

JavaScript frontend frameworks

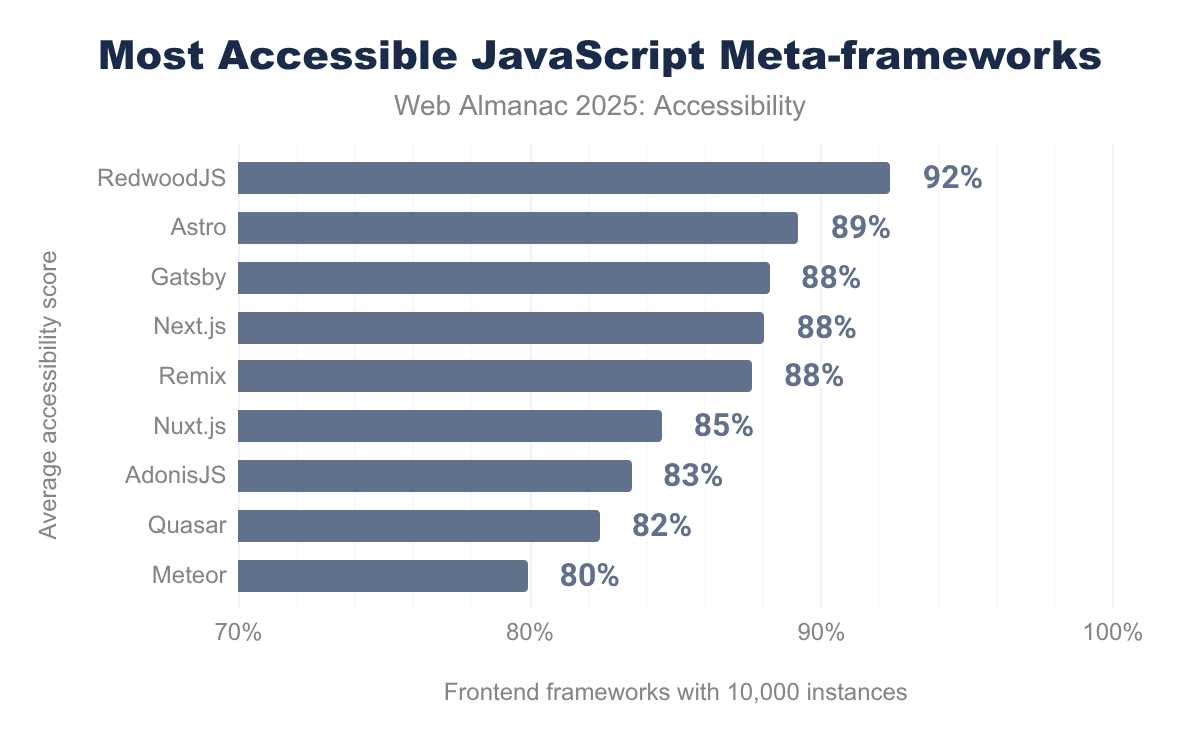

The choice of JavaScript framework also significantly influences a website’s accessibility outcomes. Using classifications from the State of JS report, we examined how different UI frameworks and meta-frameworks correlate with accessibility performance. This revealed patterns, shifts, and emerging concerns.

In 2025, OpenUI5 has risen in accessibility rankings, while frameworks that led in 2024 (Stimulus, Remix, and Qwik) have shifted positions. Remix appears in both UI and meta-framework categories, but has declined in rankings in 2025, allowing other frameworks to advance. This volatility may reflect sample size changes or real improvements in competing frameworks. The fact that all Remix functionality was integrated right into the next version of React Router, making Remix redundant as a React framework, can also have an impact on rankings.

Historically, Stimulus, Remix, and Qwik outperformed mainstream options like React, Svelte, or Ember.js by several percentage points, likely because they prioritize progressive enhancement and semantic HTML.

Among meta-frameworks, Remix, RedwoodJS, and Astro led in 2024, with Remix’s decline allowing Gatsby to rise to third place in 2025. The rise of server-first meta-frameworks (SvelteKit, Astro, Remix, Qwik, Fresh, Analog) reflects a broader industry shift toward better performance and accessibility practices by reducing client-side JavaScript complexity.

The choice of library also has an impact on accessibility.

React offers maximum flexibility and customization, but requires developers to intentionally implement accessibility. Its extensive ecosystem includes accessibility-focused libraries like React Aria and Reach UI, but accessibility isn’t enforced by default.

Angular provides strong built-in accessibility features, structured conventions that promote semantic HTML, ARIA attribute support, and Material Design components with keyboard navigation and screen reader support out-of-the-box. Angular’s opinionated structure tends to guide developers toward more standardized, accessible practices.

Vue.js aims to strike a balance between React’s flexibility and Angular’s structure. Vue’s progressive design, clear template syntax, and component architecture support accessibility, though it relies more on developer discipline and third-party plugins like vue-a11y.

We also note that GitHub took the Global Accessibility Awareness Day (GAAD) pledge to improve open source accessibility at scale. This commitment addresses a critical gap: 90% of companies use open source, 97% of codebases contain open source components, and an estimated 70–90% of code within commercial tools derives from open source.

RedwoodJS remains the most accessible, followed by Astro and Gatsby.

Conclusion

The 2025 Web Almanac accessibility analysis reveals a year of incremental progress, tempered by significant challenges and missed opportunities.

Automated testing remains essential for assessing accessibility at scale. But the data demonstrates that measurement alone doesn’t guarantee meaningful improvement. The web community must move beyond basic compliance metrics to address the systemic issues that continue to exclude millions of users with disabilities.

The most notable improvements in 2025 emerged in sectors and regions where regulatory pressure and enforcement mechanisms are strongest. However, the lack of dramatic improvement following the European Accessibility Act’s June 28, 2025, deadline is instructive. The full impact may not be apparent until 2026 and beyond.

The rapid rise of the .ai domain to among the most accessible TLDs reflects an important pattern. Newer, venture-backed technology companies tend to build with modern accessibility practices from the start, whereas legacy websites often remain inaccessible. This proves that accessibility is achievable when prioritized early in development.

Despite improvements in specific areas, the core accessibility barriers identified in 2024 persist largely unchanged in 2025.

Color contrast, link naming, heading hierarchy, and image alt text remain the top four issues across nearly every platform and framework. These aren’t failures directly of the tool, but how the authors use them. Authors have some role in all of these failures according to the W3C’s Accessibility Roles and Responsibilities Mapping (ARRM).

This reality reveals a critical insight. CMS platforms, JavaScript frameworks, and web technologies can provide accessibility foundations, but they can’t force content creators to make accessible choices. Approaches like the Authoring Tool Accessibility Guidelines (ATAG) 2.0 and the new W3C ATAG Community Group could help.

The 2025 metrics suggest stagnation where we expected incremental improvement, highlighting the gap between what’s easy to measure and what’s easy to fix.

The continued rise of accessibility overlays (now on 2% of sites) is concerning. It seems that organizations often choose shortcuts over genuine accessibility. The IAAP and European Disability Forum have explicitly warned that overlays can interfere with users’ assistive technology and must never replace accessible design. The 2025 data confirms overlays remain concentrated in lower-traffic sites, a sign that high-quality, well-resourced organizations are moving away from them toward real solutions.

The 2025 data underscores that automation is necessary but insufficient. Lighthouse and similar tools detect easily measurable violations, yet 50% of images on the web have empty or inadequate alt text. Heading hierarchy can be audited, but semantic meaningfulness requires human judgment. Color contrast can be checked, but visual design choices involve subjective artistic decisions informed by accessibility requirements.

Our 2025 findings reveal a web that remains largely inaccessible for millions of people with disabilities.

While incremental improvements in specific areas offer encouragement, persistent gaps in color contrast, link naming, heading structure, and image descriptions demonstrate that the web community hasn’t yet made accessibility a genuine priority.

The rise of .ai domains, GitHub’s open source pledge, and regulatory deadlines like the EU Accessibility Act and ADA Title II final rule offer hope that 2026 may see more substantial change. That’s only if organizations move beyond measurement to accountability, from rhetoric to resources, and from compliance to genuine inclusion.

The web should work for everyone. Until that principle guides our design, development, and deployment decisions, the accessibility gaps documented in this report will persist.